Amazingly, I don't think I've ever blogged about video games and sexism. I suppose that I don't say much about video games because I really don't play many of them. (I mean, I've owned every Nintendo console but the Wii U, but I wouldn't call myself a gamer and I don't think that would qualify me, regardless.) But it's still a bit odd, isn't it? Anyway.

You've probably heard about Anita Sarkeesian, or are at least familiar with her Tropes Vs. Women series of videos. (And if not that, you've probably noticed that the heroes and villains in most video games are men, and that women are often reduced to the role of victim, prize, or simply eye candy. Right? Right.) For her effort, Sarkeesian has been threatened with rape and murder by dozens (hundreds? thousands?) of male video game fans, who perceive the criticism of their games as personal attacks. There have been apps that simulate beating her up, attempted hacks of her Twitter and Google accounts, threats against her family, and bomb threats preceding her speaking engagements. She's had to call the police, had a case referred to the FBI for further investigation, and briefly went into hiding, recently.

Let me spell out the irony, if it isn't already painfully obvious: Sarkeesian points out that video games are dominated by narratives of masculine violence and feminine submission; her critics, who deny the veracity of her claims, demand her submission and threaten her with violence. No, really. You can't make this shit up.

Anyway, a month ago, my brothers and I attended Fan Expo Canada in Toronto. It's a geek convention - comic books, anime, and video games, mostly - and one of my brothers wore this:

Needless to say, I think, this shirt is about as controversial as it gets at a geek convention. A lot of people feel strongly that Sarkeesian is right or that she's wrong. And when these people who strongly feel she's right speak up and say so? They're also sometimes threatened with rape and death.

Well, some of them are threatened, at least. When an activist named Stephanie Guthrie spoke out against the 'Beat Up Anita Sarkeesian' game, she was also threatened, repeatedly and by multiple people. And so, as my brother walked around this convention with a shirt that practically begged people to threaten him with rape and death - and almost immediately posted pictures of it to Twitter and Facebook, increasing the likelihood that the right/wrong people would see it - I wondered... would this muscular, tattooed white dude get even a fraction of the same response?

So, I gave it a month. Five weeks to see whether anyone would bat an eye, whether the guys claiming that Sarkeesian was the real sexist would prove themselves equal opportunity harassers. And our friends were curious, too. Here are the first two responses to the picture on Facebook:

The finally tally on Twitter? 419 Retweets, 1264 Favorites. Two jokes that he should ask for a refund. (Though these responses were made in response to me, not him.) One accusation that he was being a "white knight". And one threat of a "shanking". That's it - and the tweet seems to have since disappeared.

My brother also told people that he received nothing but compliments - most notably from Sex Criminals artist Chip Zdarsky, aka Steve Murray - but this isn't entirely true. Sure, everyone who spoke to him complimented the shirt. What he didn't see, though, were the sideways glares and glowers, which usually only happened after he had passed by and which I noticed because I was sometimes walking behind him. I only saw a half-dozen or so of these, but I wasn't paying exceptionally close attention. It was clear that the shirt surprised, annoyed, and/or upset some people. It just didn't surprise, annoy, or upset them enough to say or do anything to the guy who was wearing it. (I won't explicitly speculate as to why that is. I'll leave that part up entirely up to you. Give it a try. It's just as easy as it seems!)

So, the negative reactions were there. They just weren't particularly loud or threatening or... anything, really. Just deafening silence.

Showing posts with label cultural studies. Show all posts

Showing posts with label cultural studies. Show all posts

Sunday, October 05, 2014

Thursday, May 23, 2013

White male privilege in Star Trek: no single person's responsibility, but everyone's problem

I haven't seen Star Trek: Into Darkness - I plan to, eventually - but this article about Star Trek's failure to live up to its credo of diversity and tolerance (if not acceptance) makes some broader points that, I suspect, apply equally well to the new film. The money quote:

I wrote a short blog about this a few years ago, when I was commenting on both the remarkable racism - at least, in light of its purported progressive values - of The Next Generation and, yet, its oddly satisfying conclusion, where the producers argue that the progress narrative is deeply hypocritical and masks a root savagery that we'll never fully shake. (Deep Space Nine would pick this idea up and really run with it, positing that the more civilized the exterior appears, the more rotten it is at its core. Which, funny enough, seems to be exactly the argument that George R.R. Martin is putting forward with A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones.)

But the part of that article that I wanted to respond to, specifically, is where the author makes reference to the absence of gay characters and the explanations offered by current and former writers/producers Ronald D. Moore and J.J. Abrams. And we can add one from former show-runner Brannon Braga, too:

So, each comment amounts to "we didn't really think about it", though with varying degrees of self-awareness and self-reflexivity. Braga seems to recognize, at least tacitly, that straight male privilege was preventing them from even considering it. Abrams, on the other hand, doesn't seem to realize how problematic it is to situate gay relationships as "distractions" when straight relationships wouldn't be similarly interrogated.

Anyway, this reminded me of the critiques of Girls and Game of Thrones, when each of those shows debuted. People complained (fairly) that Girls manages to almost completely whitewash one of the most racially-diverse cities in the world. People complained (fairly) that Game of Thrones reduces ethnic Others to almost comically barbaric stereotypes. These shows, the critics said, need to be more inclusive.

The defenders of these shows replied (again, fairly) that it is not their responsibility to be inclusive - they're telling a story, and telling it the best way they know how. And this is where I see the overlap with the Star Trek quotes above. Presumably, if someone were to push particularly hard - and I think you can actually see this if you read the full Abrams interview - they would fall into a sort of rhetoric of 'it's not my/our job to be everything to everyone', and making media for straight white dudes is a relatively easy sell. And, again, on an individual basis, they would be right.

The problem is, no one thinks it's their job to make a multicultural Girls, a racially-sensitive Game of Thrones, or a gay Star Trek character. Well, not "no one", but certainly very few people - and certainly not anyone with mainstream prominence. And while it may not be any single person's responsibility, it is our collective responsibility to ensure that real people see their lives reflected in real representations.

And that's the catch-22 - there's a collective obligation and need, here, but you can't force a J.J. Abrams or George R.R. Martin to be more inclusive, individually. (Well, maybe you can argue that Star Trek requires that the guy at the helm prove that it deserves its reputation. Maybe.) Yet, it's obvious that individual action - and accompanying monetary success - is the only thing that can lead to change among the wider entertainment industry. But while something needs to change, no one person is required to be the person who does it. So, no one does.

And that's why we just keep complaining.

"The reality is that, at best, Star Trek is like a well-meaning but misguided friend who thinks that they are far more progressive than they actually are. Depending on the topic and franchise, Star Trek’s track record varies from 'mediocre but still better than most other shows of its era' to 'fucking hypocritical bullshit that makes me swear at the TV.'"

I wrote a short blog about this a few years ago, when I was commenting on both the remarkable racism - at least, in light of its purported progressive values - of The Next Generation and, yet, its oddly satisfying conclusion, where the producers argue that the progress narrative is deeply hypocritical and masks a root savagery that we'll never fully shake. (Deep Space Nine would pick this idea up and really run with it, positing that the more civilized the exterior appears, the more rotten it is at its core. Which, funny enough, seems to be exactly the argument that George R.R. Martin is putting forward with A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones.)

|

| Actual shot from the most embarrassingly racist episode of TNG. |

But the part of that article that I wanted to respond to, specifically, is where the author makes reference to the absence of gay characters and the explanations offered by current and former writers/producers Ronald D. Moore and J.J. Abrams. And we can add one from former show-runner Brannon Braga, too:

“The truth is it was not really a priority for any of us on the staff so it wasn’t really something that was strong on anybody’s radar.... Somebody has to decide that it’s important before you do it.” (Moore)

"I think it was, not so much a young man’s [issue], it was a syndicated family show, showing at six o’clock, you know, in Salt Lake City, so you had to deal with each separate affiliate rather than one network. And things like that. It was not a forward thinking decision. Knowing the players involved, knowing the decision makers, knowing it was that they felt reluctant about, you know, we’re not saying 'yes,' we’re not saying 'no,' we’re not just not going to touch that right now." (Braga)

"I just wouldn’t want the agenda to be-- whether it’s a heterosexual relationship or a homosexual relationship, to tell a story that was, that felt distracting from part of the purpose of the story is. ...this was not in the list of my priorities to try to figure out how to make this movie in the best possible way. But it will now be in the hopper. And it’s one of those things I’ll bring up with the writers next time we meet." (Abrams)

So, each comment amounts to "we didn't really think about it", though with varying degrees of self-awareness and self-reflexivity. Braga seems to recognize, at least tacitly, that straight male privilege was preventing them from even considering it. Abrams, on the other hand, doesn't seem to realize how problematic it is to situate gay relationships as "distractions" when straight relationships wouldn't be similarly interrogated.

Anyway, this reminded me of the critiques of Girls and Game of Thrones, when each of those shows debuted. People complained (fairly) that Girls manages to almost completely whitewash one of the most racially-diverse cities in the world. People complained (fairly) that Game of Thrones reduces ethnic Others to almost comically barbaric stereotypes. These shows, the critics said, need to be more inclusive.

The defenders of these shows replied (again, fairly) that it is not their responsibility to be inclusive - they're telling a story, and telling it the best way they know how. And this is where I see the overlap with the Star Trek quotes above. Presumably, if someone were to push particularly hard - and I think you can actually see this if you read the full Abrams interview - they would fall into a sort of rhetoric of 'it's not my/our job to be everything to everyone', and making media for straight white dudes is a relatively easy sell. And, again, on an individual basis, they would be right.

The problem is, no one thinks it's their job to make a multicultural Girls, a racially-sensitive Game of Thrones, or a gay Star Trek character. Well, not "no one", but certainly very few people - and certainly not anyone with mainstream prominence. And while it may not be any single person's responsibility, it is our collective responsibility to ensure that real people see their lives reflected in real representations.

And that's the catch-22 - there's a collective obligation and need, here, but you can't force a J.J. Abrams or George R.R. Martin to be more inclusive, individually. (Well, maybe you can argue that Star Trek requires that the guy at the helm prove that it deserves its reputation. Maybe.) Yet, it's obvious that individual action - and accompanying monetary success - is the only thing that can lead to change among the wider entertainment industry. But while something needs to change, no one person is required to be the person who does it. So, no one does.

And that's why we just keep complaining.

Friday, March 01, 2013

Why Seth McFarlane wasn't funny and why the Onion was

Given that the turnaround for commentary on award shows is now, like, 12 hours, this is at least several days late. So, I apologize for my tardiness.

1. The Seth MacFarlane controversy

Seth MacFarlane was pretty awful, but I don't really have to tell you that. Instead, I can point you in the direction of a few links: you can find a list of sexist jokes here, a description of the sexism fatigue that sets in when one finds him/herself constantly fighting against defenses of sexism, and another perspective that didn't think the jokes were particularly bad but found MacFarlane's reduction of Halle Berry to merely a "beautiful woman" insulting. What emerges, even though many of the articles disagree over the specifics, is a general agreement about the "banality of sexism".

Because the problem isn't any one individual joke or comment that came from MacFarlane, which, in their isolation, might very well have seemed funny. The problem was 1) an unceasing barrage of mean-spirited jokes about women and 2) the relative absence of gendered jokes at the expense of men. And what that contributes to is a feeling that this kind of differential is simply normal. And if it seems like it's not a big deal, that's only because we're numb to what the jokes and comments actually mean. To wit, if we don't think it's problematic to describe Halle Berry only in terms of her beauty, rather than her talent, that's because we're entirely too accustomed to valuing women for their beauty, and only their beauty. It might be a compliment, but it's effectively a back-handed one.

2. The Onion controversy

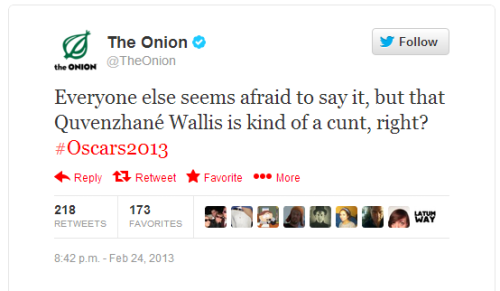

This got less attention. The Onion was live-tweeting the Oscars, and this was one of those tweets:

Quvenzhané Wallis, if you didn't follow the show or watch Beasts of the Southern Wild, is a 9 year-old, and the reaction to the joke was so very swift and very negative that the Onion quickly pulled the tweet and apologized.

The thing is... I actually think this joke is hilarious. For one, the Onion isn't Seth MacFarlane - who made his own joke about Wallis, a worse one, that implied she was nearly old enough for George Clooney to date - and they have substantially more cred when it comes to gender-based humor. For another, the joke is both good satire (this is exactly the kind of crap that tabloids actually write...) and hilariously absurd (...but it's also the basest, most extreme version of that same tabloid crap). The joke works because no one would say that this 9 year-old girl is a "cunt".

And the joke also works because it isn't actually about Wallis - it's actually about the vacuity and mean-spiritedness of entertainment journalism and, more generally, the sort of people who thoughtlessly slap these sorts of misogynist labels on all women. This is also why MacFarlane's jokes are bad - he finds humor in victimization and oppression (see: his Rhianna and Chris Brown joke) rather than poking fun at the oppressors. (Admittedly, this is where the Wallis joke is shakiest. It could be read as making fun of her, certainly. But the best jokes also have to walk that sort of delicate line.)

And, as such, it actually does a pretty effective job of peeling back that layer of banality that insulates discourses of sexism. This might very well be something that no one would say, but it sounds suspiciously similar to things that people say all the time.

Now, admittedly, this is a pretty meta-level justification. And if people find this distasteful and unacceptable, I get it. But that's also kinda the point. Good satire scores political points by way of establishing its similarity to something real that's different in degree, not type. So, if you can't buy into the sexism of this joke, you shouldn't buy into the sexism that underlies those other jokes. That is, you should be able to see that the problem isn't how the Onion called this 9 year-old a "cunt" - the problem is that we think it's cool to call anyone a "cunt". Or sing about their boobs. Or how they had to develop eating disorders in order to fit into their dresses.

1. The Seth MacFarlane controversy

Seth MacFarlane was pretty awful, but I don't really have to tell you that. Instead, I can point you in the direction of a few links: you can find a list of sexist jokes here, a description of the sexism fatigue that sets in when one finds him/herself constantly fighting against defenses of sexism, and another perspective that didn't think the jokes were particularly bad but found MacFarlane's reduction of Halle Berry to merely a "beautiful woman" insulting. What emerges, even though many of the articles disagree over the specifics, is a general agreement about the "banality of sexism".

Because the problem isn't any one individual joke or comment that came from MacFarlane, which, in their isolation, might very well have seemed funny. The problem was 1) an unceasing barrage of mean-spirited jokes about women and 2) the relative absence of gendered jokes at the expense of men. And what that contributes to is a feeling that this kind of differential is simply normal. And if it seems like it's not a big deal, that's only because we're numb to what the jokes and comments actually mean. To wit, if we don't think it's problematic to describe Halle Berry only in terms of her beauty, rather than her talent, that's because we're entirely too accustomed to valuing women for their beauty, and only their beauty. It might be a compliment, but it's effectively a back-handed one.

2. The Onion controversy

This got less attention. The Onion was live-tweeting the Oscars, and this was one of those tweets:

Quvenzhané Wallis, if you didn't follow the show or watch Beasts of the Southern Wild, is a 9 year-old, and the reaction to the joke was so very swift and very negative that the Onion quickly pulled the tweet and apologized.

The thing is... I actually think this joke is hilarious. For one, the Onion isn't Seth MacFarlane - who made his own joke about Wallis, a worse one, that implied she was nearly old enough for George Clooney to date - and they have substantially more cred when it comes to gender-based humor. For another, the joke is both good satire (this is exactly the kind of crap that tabloids actually write...) and hilariously absurd (...but it's also the basest, most extreme version of that same tabloid crap). The joke works because no one would say that this 9 year-old girl is a "cunt".

And the joke also works because it isn't actually about Wallis - it's actually about the vacuity and mean-spiritedness of entertainment journalism and, more generally, the sort of people who thoughtlessly slap these sorts of misogynist labels on all women. This is also why MacFarlane's jokes are bad - he finds humor in victimization and oppression (see: his Rhianna and Chris Brown joke) rather than poking fun at the oppressors. (Admittedly, this is where the Wallis joke is shakiest. It could be read as making fun of her, certainly. But the best jokes also have to walk that sort of delicate line.)

And, as such, it actually does a pretty effective job of peeling back that layer of banality that insulates discourses of sexism. This might very well be something that no one would say, but it sounds suspiciously similar to things that people say all the time.

Now, admittedly, this is a pretty meta-level justification. And if people find this distasteful and unacceptable, I get it. But that's also kinda the point. Good satire scores political points by way of establishing its similarity to something real that's different in degree, not type. So, if you can't buy into the sexism of this joke, you shouldn't buy into the sexism that underlies those other jokes. That is, you should be able to see that the problem isn't how the Onion called this 9 year-old a "cunt" - the problem is that we think it's cool to call anyone a "cunt". Or sing about their boobs. Or how they had to develop eating disorders in order to fit into their dresses.

Saturday, October 13, 2012

LHN: In 2013, the world will turn bronze

So, there was a fashion insert in NOW Magazine this week, and I saved it because it the ad on the back over unsettled me. And it unsettled me because, in spite of the obvious attempt to include a racially diverse group of lads and ladies, they are all the exact same colour:

The company, by the way, is called Look Hot Naked. And no, I have no idea what the product is - they're building the brand before they even tell us what they're selling. Which is effective, I suppose - earlier today, Victoria and I were talking about how well a similar approach worked for IOGO, the yogurt company. Personally, though? I find it annoying.

But whatever it is? It turns hot people into a uniform-bronze. (There's an academic paper here. And no, it's probably not flattering.)

The company, by the way, is called Look Hot Naked. And no, I have no idea what the product is - they're building the brand before they even tell us what they're selling. Which is effective, I suppose - earlier today, Victoria and I were talking about how well a similar approach worked for IOGO, the yogurt company. Personally, though? I find it annoying.

But whatever it is? It turns hot people into a uniform-bronze. (There's an academic paper here. And no, it's probably not flattering.)

Thursday, August 09, 2012

Olympic soccer: rules and dives

Two quick responses to Olympic women's soccer:

1) Without getting into too much detail - because if you care, you already know; and if you don't, you can just read about it here - a semi-final game in Olympic soccer might have been decided by a referee's decision to invoke an arcane and rarely used rule that says a goalkeeper can't hold on to the ball for more than 6 seconds. (How rare and arcane? Apparently, no sports writer can find mention of it in an international or major domestic league game - men's or women's - since 2002. That's ten years, and probably tens of thousands of games.) What makes this rule especially damaging is that the opposing team is awarded a free-kick directly in front of the goal.

For baseball fans, this would be like enforcing the "12-second" rule for pitchers. What "12-second" rule, you ask? The one that's never actually used, yet remains in the rulebook:

Hilariously, the average pitcher in Major League Baseball is nowhere near the ostensible "limit" of 12 seconds per possession - it's actually more like 20. And yet, an umpire could suddenly decide to call this rule, and the pitcher would have no substantive reason to object, except on the grounds that no one calls it. Which is simply a disaster waiting to happen. If officials don't use it, the rulebook should lose it.

2) I often find men's soccer painful to watch. It's the diving. I just can't stand to watch people pretend to be fouled and then pretend to be hurt. And I like watching women's soccer because it there's almost none of that. And not only is there virtually no diving, but it seems like these women will collide and run over each other and get right back up - to put it simply, they 'suck it up'.

At first, this seems really unintuitive. We expect women's sports to have (patronizing) rules in place to protect them - women's hockey, for instance, doesn't allow body checking at any level - and we expect, in North America, at least, that men will behave in typically masculine ways and eschew diving or any other behavior that might make them seem weak.

That last bit might be the important part, though. When I was watching Canada play Great Britain, the commentators suggested that the stylistic difference between the women's and men's games was cultural - the women's game, and it's first powerhouse-teams - emerged in the USA and East Asia, where diving in any sport has never been valued, and those values were emulated by other countries. Now, I don't know that this is an adequate explanation. Most of the women's teams are coached and trained by European men, after all. But it's certainly interesting. (And certainly problematic, since it's that masculine ethic of playing through the pain and self-destructive behavior that I've criticized again and again. And which, clearly, I value in spite of that.)

1) Without getting into too much detail - because if you care, you already know; and if you don't, you can just read about it here - a semi-final game in Olympic soccer might have been decided by a referee's decision to invoke an arcane and rarely used rule that says a goalkeeper can't hold on to the ball for more than 6 seconds. (How rare and arcane? Apparently, no sports writer can find mention of it in an international or major domestic league game - men's or women's - since 2002. That's ten years, and probably tens of thousands of games.) What makes this rule especially damaging is that the opposing team is awarded a free-kick directly in front of the goal.

For baseball fans, this would be like enforcing the "12-second" rule for pitchers. What "12-second" rule, you ask? The one that's never actually used, yet remains in the rulebook:

8.04 When the bases are unoccupied, the pitcher shall deliver the ball to the batter within 12 seconds after he receives the ball. Each time the pitcher delays the game by violating this rule, the umpire shall call “Ball.” The 12-second timing starts when the pitcher is in possession of the ball and the batter is in the box, alert to the pitcher. The timing stops when the pitcher releases the ball.

Hilariously, the average pitcher in Major League Baseball is nowhere near the ostensible "limit" of 12 seconds per possession - it's actually more like 20. And yet, an umpire could suddenly decide to call this rule, and the pitcher would have no substantive reason to object, except on the grounds that no one calls it. Which is simply a disaster waiting to happen. If officials don't use it, the rulebook should lose it.

* * *

2) I often find men's soccer painful to watch. It's the diving. I just can't stand to watch people pretend to be fouled and then pretend to be hurt. And I like watching women's soccer because it there's almost none of that. And not only is there virtually no diving, but it seems like these women will collide and run over each other and get right back up - to put it simply, they 'suck it up'.

At first, this seems really unintuitive. We expect women's sports to have (patronizing) rules in place to protect them - women's hockey, for instance, doesn't allow body checking at any level - and we expect, in North America, at least, that men will behave in typically masculine ways and eschew diving or any other behavior that might make them seem weak.

That last bit might be the important part, though. When I was watching Canada play Great Britain, the commentators suggested that the stylistic difference between the women's and men's games was cultural - the women's game, and it's first powerhouse-teams - emerged in the USA and East Asia, where diving in any sport has never been valued, and those values were emulated by other countries. Now, I don't know that this is an adequate explanation. Most of the women's teams are coached and trained by European men, after all. But it's certainly interesting. (And certainly problematic, since it's that masculine ethic of playing through the pain and self-destructive behavior that I've criticized again and again. And which, clearly, I value in spite of that.)

Sunday, July 22, 2012

More backlash politics: fanboys and the "triumph" of Superheroes

I can't believe I missed the whole backlash against AO Scott in The New York Times, because he deigned to criticize The Avengers film, but it seems additionally relevant now - because of the controversy with hardcore gamers that I wrote about last week, but probably also because of what happened in Colorado.

Actually, Scott's snarky review was probably meaner to the film's fans that it was to the movie itself. Writes Scott,

So, there is a not-flattering comparison to Transformers, though this isn't as nasty as it might first seem - if Transformers did anything competently, if not creatively, it was show things exploding. But there is a certain nastiness in the review, and it's aimed squarely at the fans. For instance:

Yikes. It's not terribly surprising, then, that Scott was flamed over Twitter by fanboys with demands that he be fired. (Having not read them, I can't be certain whether these were people who were responding to ostensible insult of the film or the more real insult to themselves. If it's the former, that's an unfortunate irony, because it proves that Scott's joke, above, isn't just a joke.)

Anyway, I bring this up now, and call it newly relevant, because the insecurity that those fans appear to be speaking from is a lot like the insecurity of hardcore gamers. There's a reason, after all, that fans of Marvel comics, in particular, are called Marvel Zombies. (I doubt that Scott knew this. And, yet, he clearly knew it.)

In the blog about hardcore gamers, I wrote that

To attack the Avengers film or Avengers fanboys, then, produces a similar effect. But it is also similarly problematic. Because, like most hardcore gamers, fanboys tend to be straight, middle-class white men who enjoy an incredible amount of privilege.

There's an additional layer to the comic book issue, though, one that was recently raised by Freddie deBoer. To pick from the very first line in deBoer's blog, over the past decade fanboys have learned that "our particular geeky obsessions no longer seemed special. Everyone knew about them." That's still not entirely true of gamer culture, I think. I'd wager that few people outside of the gaming community would recognize the N7 insignia that Commander Shepard wears if you slapped it on your coat (in fact, I'm not sure that they would know it has any significance at all); I'm fairly certain that a large minority or small majority of people under 40 would be familiar with Captain American's shield or the X-Men's X.

Because I'm filling this blog with quotes, I'll add another one, this time from Andrew O'Heir at Salon:

The hardcore gamers may feel as if they're under assault by hostile forces, but they remain the gatekeepers of their own online kingdom and firmly in control of their own culture. Not so, for the fanboys, who lost whatever control they once had (if they ever had it) long ago to interests in Hollywood and boardrooms, filled with people who want to diversify and grow the audience, not cater to the base. It's like the fans of the Avengers used to speak a secret language that only they understood, and now everyone and their dad uses it in casual conversation. You might call it "triumph"; one could also plausibly call it "devastating".

O'Heir concludes with the remark that "I think these fans are looking to the stars, for some sort of recognition or respect that simply doesn’t exist, for any of us." But I think that the critical misunderstanding is this - these fans aren't happy with success because they were never looking for and never wanted success. (Kurt Cobain, anyone?) They're defined by the things they appreciate that others never will, and so, in a sense, they're looking for a new defeat to rally around. (As evinced by the response to Scott.) Triumph will never be sufficient, and will never be particularly desirable, because it's difficult to feel special - and it's always been about feeling special, unique, and even superior - when everyone else loves and appreciates the same thing that you do.

|

| Hawkeye, Captain American, and the Black Widow in Joss Whedon's Avengers. Zade Rosenthal/Walt Disney Pictures. |

Actually, Scott's snarky review was probably meaner to the film's fans that it was to the movie itself. Writes Scott,

this movie revels in the individuality of its mighty, mythical characters, pinpointing insecurities that are amplified by superhuman power and catching sparks that fly when big, rough-edged egos (and alter egos) collide. The best scenes are not the overblown, skull-assaulting action sequences — which add remarkably little that will be fresh or surprising to devotees of the Transformers franchise — but the moments in between, when the assembled heroes have the opportunity to brag, banter, flirt and bicker.

So, there is a not-flattering comparison to Transformers, though this isn't as nasty as it might first seem - if Transformers did anything competently, if not creatively, it was show things exploding. But there is a certain nastiness in the review, and it's aimed squarely at the fans. For instance:

the true guiding spirit of their movie is Loki, who promises to set the human race free from freedom and who can be counted on for a big show wherever he goes. In Germany he compels a crowd to kneel before him in mute, terrified awe, and “The Avengers,” which recently opened there to huge box office returns, expects a similarly submissive audience here at home. The price of entertainment is obedience.

Yikes. It's not terribly surprising, then, that Scott was flamed over Twitter by fanboys with demands that he be fired. (Having not read them, I can't be certain whether these were people who were responding to ostensible insult of the film or the more real insult to themselves. If it's the former, that's an unfortunate irony, because it proves that Scott's joke, above, isn't just a joke.)

Anyway, I bring this up now, and call it newly relevant, because the insecurity that those fans appear to be speaking from is a lot like the insecurity of hardcore gamers. There's a reason, after all, that fans of Marvel comics, in particular, are called Marvel Zombies. (I doubt that Scott knew this. And, yet, he clearly knew it.)

|

| Painting for the Marvel Zombies comic book, by Arthur Suydam. Yes, the title is a joke. But everyone loves zombies, so it's win-win. |

In the blog about hardcore gamers, I wrote that

every man is made to feel like they're lacking in some way. But not every man is conscious of that lack. Geeks aren't only conscious of it, but they're often reminded of it. And this is a problem for them because [the game] may be the only access that they have to a sense of masculine adequacy. To take that away, then, is to threaten their very sense of themselves as men.

To attack the Avengers film or Avengers fanboys, then, produces a similar effect. But it is also similarly problematic. Because, like most hardcore gamers, fanboys tend to be straight, middle-class white men who enjoy an incredible amount of privilege.

There's an additional layer to the comic book issue, though, one that was recently raised by Freddie deBoer. To pick from the very first line in deBoer's blog, over the past decade fanboys have learned that "our particular geeky obsessions no longer seemed special. Everyone knew about them." That's still not entirely true of gamer culture, I think. I'd wager that few people outside of the gaming community would recognize the N7 insignia that Commander Shepard wears if you slapped it on your coat (in fact, I'm not sure that they would know it has any significance at all); I'm fairly certain that a large minority or small majority of people under 40 would be familiar with Captain American's shield or the X-Men's X.

Because I'm filling this blog with quotes, I'll add another one, this time from Andrew O'Heir at Salon:

at what point is the triumph of comic-book culture sufficient? Those one-time comic-book pariahs are now the dominant force in pop-culture entertainment, and their works are deemed to be not just big but also relevant and important.

The hardcore gamers may feel as if they're under assault by hostile forces, but they remain the gatekeepers of their own online kingdom and firmly in control of their own culture. Not so, for the fanboys, who lost whatever control they once had (if they ever had it) long ago to interests in Hollywood and boardrooms, filled with people who want to diversify and grow the audience, not cater to the base. It's like the fans of the Avengers used to speak a secret language that only they understood, and now everyone and their dad uses it in casual conversation. You might call it "triumph"; one could also plausibly call it "devastating".

O'Heir concludes with the remark that "I think these fans are looking to the stars, for some sort of recognition or respect that simply doesn’t exist, for any of us." But I think that the critical misunderstanding is this - these fans aren't happy with success because they were never looking for and never wanted success. (Kurt Cobain, anyone?) They're defined by the things they appreciate that others never will, and so, in a sense, they're looking for a new defeat to rally around. (As evinced by the response to Scott.) Triumph will never be sufficient, and will never be particularly desirable, because it's difficult to feel special - and it's always been about feeling special, unique, and even superior - when everyone else loves and appreciates the same thing that you do.

Tuesday, July 10, 2012

The Feminist Frequency backlash: Explaining, not excusing or defending

If you're a part of nerd culture, if you play video games, or if you're remotely interested in gender issues, I don't need to bother summarizing what's happened, recently, with Anita Sarkeesian (of Feminist Frequency fame - we were also, briefly, in the same department at York University, though our paths never crossed) and her campaign to raise money for her 'Tropes vs. Women in Video Games' web series. But I'll summarize it, ever so briefly, anyway: she plans to talk about how misogynistic video games are, a bunch of game-playing misogynists call her names, and the rest of the internet notes that this is somewhat ironic. In more extreme cases, those misogynist gamers create games where they (and you) can vent some of your misogynist rage on Sarkeesian's likeness. Classy.

(I can't help but point out the similarities between what's happened to Sarkeesian and the misogynist video game writer who mocked Felicia Day and her nerd-credentials on Twitter. Also, this. I don't think it's a coincidence that they faced these attacks almost simultaneously. Something has snapped in that particular corner of the interwebs. And I don't think it's over yet, either.)

Now, I've been plenty critical of geek-culture myself - in spite of my claims to be a part of it - because there is plenty to criticize. But I think that we're doing ourselves a disservice if we chalk up the response to women like Sarkeesian and Day as just another instance of boilerplate misogyny. There's something else going on, here.

That something else, I think, has to do with a shared (to some extent) experience of oppression. Because, and I don't think this is going to shock anyone, men who actively identify as gamers and geeks tend to be grown-up - or growing-up - versions of kids who have been socially ostracized and victimized by their more normatively masculine (and, I should add, feminine) peers. Now, this is absolutely not the same thing as being a victim of sexism or misogyny - geeky men still, for the most part, will pass as men and be able to access varying degrees of masculine and heteronormative privilege, and many of them enjoy class and race privilege, too - but it goes a long way in explaining why the reaction to Sarkeesian has been so rabid.

Put simply, Sarkeesian is poking at a raw wound and, not unlike cornered animals, the male gamers are lashing out instinctively. Gamers, if I can generalize, participate in a performative culture of excessive masculinity precisely because they can't access that masculinity in "real" life. And, for the most part, they - unlike the purveyors of equally excessive and performative "real" masculinity - realize that it's a performance, that it's a novel and entertaining way of addressing some lack. (To be clear: every man is made to feel like they're lacking in some way. But not every man is conscious of that lack. Geeks aren't only conscious of it, but they're often reminded of it.) And this is a problem for them because it may be the only access that they have to a sense of masculine adequacy. To take that away, then, is to threaten their very sense of themselves as men.

That "sense of themselves as men", of course, is a hugely probematic one. Again, this is an explanation, not a defense - I'm not going to defend a practice of identity-building that's predicated on hyper-aggression and the objectification of women. But I do want to suggest that the where men who feel "manly" in other aspects of their lives can survive the attack on sexism in videogames, it might not be so easy for men who don't - and how have been made to feel all the more inadequate by that first category of men.

And for that reason, the existence of this misogyny and the defense of it isn't surprising - the history of the world's oppressed people is full of these seeming contradictions, where the once oppressed respond to their empowerment by turning on and oppressing the people immediately below or beside them on the totem pole: think of how political franchise movements in the USA pitted black men against black women or white women against black women, rather than all three against white men; the reputation that communities of gay men have for misogyny; or even how the little kids who get bullied by big kids will bully the little kids when they themselves get bigger. (An even more direct comparison? The similar way that criticism of sexism in superhero comics has been received.) You might suspect that oppression would breed empathy, and it does to some extent and in some cases, but it's equally likely to teach people that power (male power, in this case) is most easily achieved and maintained by adopting the same tactics that were used against you.

Being bullied doesn't grant you a license to bully, though it does provide an explanation for why bullying might strike you as a reasonable response to a threat. Clearly, though, the fact that Sarkeesian's work is perceived as threatening to an entire subculture would seem to suggest that we've missed something - that it's not enough to point out that geek culture is misogynist, and expect that change will come quickly and easily. Because that misogyny? It's part of the core around which geek identity has been built, and removing it would be like removing sexism from patriarchy - a totally unrecognizable system, the end of geeks and men as we know them. And that, not surprisingly, might be too terrifying for them to consider.

(I can't help but point out the similarities between what's happened to Sarkeesian and the misogynist video game writer who mocked Felicia Day and her nerd-credentials on Twitter. Also, this. I don't think it's a coincidence that they faced these attacks almost simultaneously. Something has snapped in that particular corner of the interwebs. And I don't think it's over yet, either.)

Now, I've been plenty critical of geek-culture myself - in spite of my claims to be a part of it - because there is plenty to criticize. But I think that we're doing ourselves a disservice if we chalk up the response to women like Sarkeesian and Day as just another instance of boilerplate misogyny. There's something else going on, here.

That something else, I think, has to do with a shared (to some extent) experience of oppression. Because, and I don't think this is going to shock anyone, men who actively identify as gamers and geeks tend to be grown-up - or growing-up - versions of kids who have been socially ostracized and victimized by their more normatively masculine (and, I should add, feminine) peers. Now, this is absolutely not the same thing as being a victim of sexism or misogyny - geeky men still, for the most part, will pass as men and be able to access varying degrees of masculine and heteronormative privilege, and many of them enjoy class and race privilege, too - but it goes a long way in explaining why the reaction to Sarkeesian has been so rabid.

Put simply, Sarkeesian is poking at a raw wound and, not unlike cornered animals, the male gamers are lashing out instinctively. Gamers, if I can generalize, participate in a performative culture of excessive masculinity precisely because they can't access that masculinity in "real" life. And, for the most part, they - unlike the purveyors of equally excessive and performative "real" masculinity - realize that it's a performance, that it's a novel and entertaining way of addressing some lack. (To be clear: every man is made to feel like they're lacking in some way. But not every man is conscious of that lack. Geeks aren't only conscious of it, but they're often reminded of it.) And this is a problem for them because it may be the only access that they have to a sense of masculine adequacy. To take that away, then, is to threaten their very sense of themselves as men.

That "sense of themselves as men", of course, is a hugely probematic one. Again, this is an explanation, not a defense - I'm not going to defend a practice of identity-building that's predicated on hyper-aggression and the objectification of women. But I do want to suggest that the where men who feel "manly" in other aspects of their lives can survive the attack on sexism in videogames, it might not be so easy for men who don't - and how have been made to feel all the more inadequate by that first category of men.

And for that reason, the existence of this misogyny and the defense of it isn't surprising - the history of the world's oppressed people is full of these seeming contradictions, where the once oppressed respond to their empowerment by turning on and oppressing the people immediately below or beside them on the totem pole: think of how political franchise movements in the USA pitted black men against black women or white women against black women, rather than all three against white men; the reputation that communities of gay men have for misogyny; or even how the little kids who get bullied by big kids will bully the little kids when they themselves get bigger. (An even more direct comparison? The similar way that criticism of sexism in superhero comics has been received.) You might suspect that oppression would breed empathy, and it does to some extent and in some cases, but it's equally likely to teach people that power (male power, in this case) is most easily achieved and maintained by adopting the same tactics that were used against you.

Being bullied doesn't grant you a license to bully, though it does provide an explanation for why bullying might strike you as a reasonable response to a threat. Clearly, though, the fact that Sarkeesian's work is perceived as threatening to an entire subculture would seem to suggest that we've missed something - that it's not enough to point out that geek culture is misogynist, and expect that change will come quickly and easily. Because that misogyny? It's part of the core around which geek identity has been built, and removing it would be like removing sexism from patriarchy - a totally unrecognizable system, the end of geeks and men as we know them. And that, not surprisingly, might be too terrifying for them to consider.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Mad Men: misogyny and tragedy

I wanted to write something quick and dirty about the moralizing tone of Mad Men and how, ultimately, it will or should end. (I should add that this is inspired, somewhat, by these two very different critiques of the show and its feelings about and representation of the misogyny of its era.)

The author of the Gawker essay doesn't miss the point of the show, exactly, so much as he fails to see the big picture. Mad Men is sexy, yes, and its world is oozing with masculine entitlement. And, unavoidably, it makes that masculism sexy, too.

But that's not all that it's doing, because even when the show is endorsing a character, a philosophy, or a behavior, (think: Peggy) it's also always ambivalent about them (think: the final shot of Peggy in this season). As much as it might celebrate machismo, it undercuts and emasculates those same masculine men even more frequently:

It's a tragedy, but a classical one. I suppose that it's also tragic in the more contemporary sense - we do feel sympathy for Roger and Don (and even for Pete, sometimes) when things go wrong. But we're also given the sense that they're all their own worst enemies. It's their hubris, more than anything else, that's responsible for their failures and the decline of their world that we, the viewers, know is inevitable. Because they have no idea that another world is possible, and that men like them won't live forever. We, on the other hand, know that the clock is ticking. And that's why the show isn't an endorsement or celebration - it's a cautionary tale.

The author of the Gawker essay doesn't miss the point of the show, exactly, so much as he fails to see the big picture. Mad Men is sexy, yes, and its world is oozing with masculine entitlement. And, unavoidably, it makes that masculism sexy, too.

But that's not all that it's doing, because even when the show is endorsing a character, a philosophy, or a behavior, (think: Peggy) it's also always ambivalent about them (think: the final shot of Peggy in this season). As much as it might celebrate machismo, it undercuts and emasculates those same masculine men even more frequently:

- Pete Campbell cheats on his wife and is sadder for it

- he becomes more successful and confident in business, and it leads to an impromptu boxing match that he loses decisively

- Don appears to realize that his happiness always comes at the expense of the happiness of those around him, and vice versa

- Roger's loss of business acumen and relevance coincides with his LSD-fueled realization that other people have feelings, which seems to say a lot about how business works.

It's a tragedy, but a classical one. I suppose that it's also tragic in the more contemporary sense - we do feel sympathy for Roger and Don (and even for Pete, sometimes) when things go wrong. But we're also given the sense that they're all their own worst enemies. It's their hubris, more than anything else, that's responsible for their failures and the decline of their world that we, the viewers, know is inevitable. Because they have no idea that another world is possible, and that men like them won't live forever. We, on the other hand, know that the clock is ticking. And that's why the show isn't an endorsement or celebration - it's a cautionary tale.

Wednesday, June 06, 2012

Too hot for the CSA: a book review of Anthony Synott's 'Re-thinking Men'

[A little over two years ago, I requested a review copy of sociologist Anthony Synott's new book, Re-thinking Men: Heroes, Villains and Victims from the Canadian Sociological Association. The review that I submitted to the CSA was never published, and no one ever told me why. The review that appears below, then, is the one that I submitted to them. (It's a second draft. The first was, frankly, much meaner - and by that I actually mean "honest" - but I don't have a copy of it.) It's not timely, but at least it's finally seeing the light of day.]

ANTHONY SYNNOTT,

Re-thinking men: heroes, villains and victims. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. 2009, 297

p., index.

In Re-Thinking Men:

Heroes, Villains and Victims, Anthony Synnott argues for the need to

recognize men’s “massive and heroic contributions to social life and to

civilization” (4) within an “age of misandry” (102) which, he claims, has seen

men and masculinity devalued. Misandry, Synnott explains, is to men as misogyny

is to women – that is, the systemic promotion of the fear and/or hatred of men

– and the past half century has seen an increase in the prevalence and

acceptance of misandric thought, expression, and legislation. To this end,

Synnott deploys a multidisciplinary approach that considers sources as diverse

as television sitcoms and poststructural gender theory in the service of

recuperating men and masculinity and admonishing the anti-male feminisms which,

he argues, are largely to blame for misandry.

Synnott’s book is perhaps most useful to scholars who are

unfamiliar with the literature on misandry, as a survey of its chief proponents

and concerns. Following a substantial literature review, Synnott builds his

argument around the chapters on ‘Heroes’ (where he “praises” men), ‘Villains’

(about those who vilify men), and ‘Victims’ (which enumerates the ways in which

men are made to suffer and are not recognized for it). In the chapter on

villains – which is largely not, as the book’s title might suggest, about

men-as-villains – Synnott traces the trajectory of what he dubs anti-male or

female supremacist feminist literature, (Greer, Dworkin, Solanas, etc.) as well

as the masculinist writers who emerged in response, such as Bly, Farrell,

Tiger, and Nathanson and Young. Among the many concerns that he expresses in

the chapter on victims, Parental Alienation Syndrome and the disproportionate

number of men in prison and/or dying prematurely – he notes that “[o]ur

cultural norms are more lethal than our germs and our guns” (191) – are

increasingly visible outside of masculinist literature, and Synnott’s

description of the problem of male suicide – “it is a civil war” (185) – seems

particularly apt.

Many

of Synnott’s critiques of particularly misandric feminisms and feminists are on-target, as are his suggestion that gender equality is not best achieved through

the vilification of, and by ignoring the systemic issues afflicting, one

gender. Synnott also makes a fine point when he notes that the emphasis on

women’s victimization has made that woundedness central to certain feminist

identities, and may very well infantalize women rather than empower them (184).

However, this thread of his argument remains largely underdeveloped. I should also add that it is not particularly new - Wendy Brown was making similar, more nuanced points about identity politics nearly 20 years ago.

The

particular feminists that Synnott charges with misandry have been

well-documented for their oppositional and sometimes hostile relations to men

and masculinity, but Synnott’s analysis does not offer anything particularly

new on this front. Nor does it acknowledge that some of the feminists he

characterizes as misandric, such as Betty Friedan, have also spoken against

misandry, and such misrepresentations damage the credibility of his argument.

His case studies are also quite dated at this point, and ignore the third-wave feminist

movement almost entirely. This is a particularly egregious error because

Synnott’s call for intersectional research that links issues of gender with

those of race and class is a tenet of third-wave feminist work. (Many, if not

most, third-wave feminists also incorporate issues of ability and sexuality

into their research, issues which are largely absent from Synnott’s critique.)

I would have appreciated a survey of more recent – and intersectional –

feminist and profeminist works, as it is not at all clear from Synnott’s choice

of mostly decades-old texts that misandry is as rampant within

institutionalized feminism as he claims.

This

said, while Synnott’s arguments are firmly grounded in a political project,

they are not so clearly grounded within a theoretical position or methodology,

and so a number of his claims are particularly vulnerable to charges of ideological

bias. Though Synnott expresses hope that his book “will contribute to our

mutual empathy, admiration and love” (270), he also asserts a right to engage

in what he dubs “competitive victimization”, since “the victimization of men

has been ignored” (212). As such, it seems fair to characterize it as polemical.

While Synnott does not dispute that (some) women are oppressed, he argues that

male oppression is greater: that women’s objectification under the male gaze is

less harmful than men’s objectification as production units or war machines

(48), that “[w]omen are harassed” but “men die” (150). Synnott’s insistence on

measuring men’s oppression against the oppressions suffered by women, a

comparison which often has the effect of diminishing the importance of latter,

is more likely to alienate feminist and pro-feminist readers than it is to

create sympathy or empathy. His points about the various crises afflicting men

would be better served if it were not made to seem that their recognition must

come at the expense of women.

With

respect to Synnott’s methodology and the parameters of his project, Synnott

refers repeatedly to events surrounding the Titanic and 9/11 disasters as proof

of male heroism – and they may very well be – but Synnott does not explain why

these two examples should be regarded as such. Without a justification for the

choice of these particular case studies – and one of them is nearly 100 years

old – it is not clear why they should be understood as exemplars of maleness or

masculinity. Similarly, it is not clear why it is only the heroes of the

Titanic and the World Trade Center that should count, and why the men

responsible for the tremendous loss of life are not simultaneously proof of

men’s arrogance and/or villainy.

Many of the methodologies and positions that Synnott does

deploy often appear to be premised on measurements of popular consensus. He

notes in his introduction that “[m]en are surely associated with far more

positives than negatives” (14), and corroborates the claim in the chapter

titled ‘Heroes’ with reference to Time’s

list of the 20th century’s most influential people – a list that is “mostly

positive” – as well as lists of Greatest Britons, Canadians, and other lists of

great men and humanitarian accomplishments. Whether all these associations are

equal, regardless of number, or Time’s

list is actually a reliable and critical indicator of men’s contributions to

the good or ill of society are questions that go unasked. Elsewhere, and

bizarrely, Synnott is not strictly consistent in applying this approach. He

admits in his chapter on power that women comprise only a tiny proportion of

murderers and serial killers, but sees fit to devote more pages to them than he

does to any specific male murderers. It is probably fair to suggest, then, that

the title of the book is not entirely apt – as much as Synnott would like you

to re-think men, he equally wants you to reappraise women.

Synnott deploys a similar common sense logic in his

chapter on ‘Men and Women: Models and Muddles’, dismissing Judith Butler’s

theory of performativity with the suggestion that “most people surely do not

believe that sex and gender are ‘radically distinct’” (87), and so Butler must

be wrong to assert that it is so. Of course, Butler would agree that most

people believe sex and gender to be synonymous – this is, in fact, central to

her argument about the persuasiveness of performativity. Gender studies

scholars will also surely take issue with the essentialism of Synnott’s

definition of masculinity. Despite his admission that biological dualisms of

gender are highly problematic (6), Synnott’s own model of masculinity grafts

them on to Connell’s theory of plural masculinities, as he posits the existence

of both it and a complementary “core masculinity” that “embraces both culture

and nature, sociology and biology” (52). It is difficult to see how Synnott is

not himself reproducing those biological dualisms that he decries.

Explanations

of Synnott’s theory of power are mostly absent from the text, which is especially

surprising given that ‘Power’ is the title of one of his chapters. He

references Michel Foucault, but only so as to argue that power constitutes a “complex

strategic situation” (213) – as opposed to simplistic notions of vertical axis

of domination and resistance – and not because Synnott’s arguments are

Foucauldian, because they are not. Like the chapter on ‘Heroes’, ‘Power’ is not

oriented toward a theorization of gender and power so much as it is to surveying

various fields – health care, education, business – and listing and counting

the spaces that men and women occupy within them. Despite his statements to the

contrary, Synnott repeatedly relies on these vertical expressions of power in

asserting that men reside disproportionately at the “pinnacles of power” and

“bottom rungs of the ladder” (5), thus claiming that men as a single class do

not have a disproportionate hold on power. But such a reductive metaphor belies

the reality of a “complex strategic situation” and hardly constitutes a systemic

assessment of gender systems and power.

To

the detriment of his analysis, Synnott also uncouples power from three of his

major topics: gender, heroism, and love. Synnott writes that the reason most

occupants of his heroes and villains lists are male is “a function of power

rather than gender” (141), as if one is not always already implicated in the

other. Elsewhere, and somewhat contradictorily, he notes that “heroism is not

about power, but love” – while becoming a hero is a function of power, the exercise

of heroism has nothing to do with it. (And in this equation, love is evidently

the opposite of power.) Synnott’s

account of heroism as sacrifice and altruism – to say nothing of his accounts

of gender and love – could also benefit from a more complex treatment.

Synnott’s

argument is perhaps most compromised by his repeated dismissal of women’s

historical oppression, his comments to this effect also often unfortunately

paired with an all too patronizing tone. Synnott is fond of suggesting that

patriarchy has “sometimes oppressed women” (58), and even suggests that it has

“perhaps in the past been oppressive of women” (72), but does little to

substantiate these claims. He also credits patriarchy with the liberation of

women and while he admits that this “need not elicit much gratitude” (58), many

will surely wonder why the liberation of women by patriarchy from

patriarchy – if, indeed, this is an accurate assessment – should elicit any gratitude.

Synnott

also does himself a disservice in his highly prejudicial characterizations of

“victim feminists” who “continually carp and whine” (115) – as opposed to the

heroes who “overcome horrendous difficulties” with “no self-pity” (117) – about

“alleged obstacles to success”, such as glass ceilings, as opposed to “real obstacles to success” (131).

Synnott’s dismissal of sexual harassment as “very rarely rape” (149) – as if

sexual harassment is only a worthy concern if it is rape – is also troubling, as is his outrageous characterization

of the damages awarded to a woman in a sexual harassment suit as “[n]ot a bad

deal for early retirement” (150). In the rare instances where Synnott

acknowledges queer and trans men and women and the ways in which they

complicate his topic, his language can even be transphobic, as he insensitively

and too jokingly notes that “thanks to surgery, we can change sex, and be a bit

of both!” (81). Such a tone is unbecoming of scholarship that purports to be

anti-oppressive.

While

Re-Thinking Men: Heroes, Villains and

Victims is aimed at scholars of gender studies in general, its polemics and

tone are unlikely to ingratiate it with the feminist and pro-feminist scholars

that tend to populate these fields. However, it may be of interest to precisely

these scholars at least insofar as it serves as an effective introduction to, and

overview of, a subfield of gender studies that is not going away. As well,

it provides a useful summary of the dangers that come with being a North

American man in the 21st century and these concerns are too often ignored. However, while Re-Thinking

Men: Heroes, Villains and Victims may succeed in bringing additional

attention to the costs associated with being a man – which are, as Synnott

claims, substantial – it is more likely to harden the battle-lines rather than

open or soften them.

Saturday, May 12, 2012

White trash and the monstrous other

It's fashionable to say that fat and fat people constitute the last socially-acceptable category of open derision and discrimination. And it's not that I disagree with the spirit of the statement - certainly, overweight and obese people are mocked and discriminated against, both in media and interpersonally, with a sometimes almost sadistic enthusiasm. It's the "last" part that I disagree with.

Because it's still equally kosher to hate on people who would be considered, for lack of a more precise descriptor, trash. I know, "precise" sounds weird to say, doesn't it? Especially because "trash" sounds unnecessarily pejorative. I use "precise" because the trash label isn't strictly a class thing, as it might first seem - not all poor people are considered trash; not all people who are called trash are necessarily poor. It's also a cultural- and/or social-capital thing. (Calling someone "new money" is, after all, a bit like saying they're trash with cash.) And, I'd add, a race thing - because trash is so overdetermined, implicates so many different levels, to call someone trash is to put them on a level so far below the racial norm that they're basically occupying another category altogether.

But why am I saying this? Mostly, I'm saying it in response to the trailer for Chernobyl Diaries, the supernatural/radioactive-monster horror movie that's being released later this month.

Now, I fully admit that I could be reading this particular film wrong. It might not be about evil mutated Ukrainian Euro-trash that not-so-subtly equates the class and culture of poor Eastern Europeans with being a homicidal monster (and I use "monster" both literally and figuratively). It might not be like The Crazies. Or The Hills Have Eyes. Or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And let's not even talk about the kinds of characters who pop up as sociopathic serial killers on Criminal Minds or the X-Files. (I don't know Jason or Freddy all that well, but I suspect that they'd fit the thesis, too.)

So, my point, simply, is that this is flying under the radar, and has been for a long time. Maybe only Nazis are used more often when the plot calls for an insanely evil white person. (Maybe.)

But prove me wrong, Chernobyl Diaries. Prove me wrong.

Because it's still equally kosher to hate on people who would be considered, for lack of a more precise descriptor, trash. I know, "precise" sounds weird to say, doesn't it? Especially because "trash" sounds unnecessarily pejorative. I use "precise" because the trash label isn't strictly a class thing, as it might first seem - not all poor people are considered trash; not all people who are called trash are necessarily poor. It's also a cultural- and/or social-capital thing. (Calling someone "new money" is, after all, a bit like saying they're trash with cash.) And, I'd add, a race thing - because trash is so overdetermined, implicates so many different levels, to call someone trash is to put them on a level so far below the racial norm that they're basically occupying another category altogether.

But why am I saying this? Mostly, I'm saying it in response to the trailer for Chernobyl Diaries, the supernatural/radioactive-monster horror movie that's being released later this month.

|

| Glad to see that the Scary Kid trope is still alive, too! |

Now, I fully admit that I could be reading this particular film wrong. It might not be about evil mutated Ukrainian Euro-trash that not-so-subtly equates the class and culture of poor Eastern Europeans with being a homicidal monster (and I use "monster" both literally and figuratively). It might not be like The Crazies. Or The Hills Have Eyes. Or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. And let's not even talk about the kinds of characters who pop up as sociopathic serial killers on Criminal Minds or the X-Files. (I don't know Jason or Freddy all that well, but I suspect that they'd fit the thesis, too.)

|

| Creepy dude in the shadows! Watch out, attractive American cultural tourist! |

So, my point, simply, is that this is flying under the radar, and has been for a long time. Maybe only Nazis are used more often when the plot calls for an insanely evil white person. (Maybe.)

But prove me wrong, Chernobyl Diaries. Prove me wrong.

Saturday, April 14, 2012

One Direction and subtle misogyny

As if it weren't bad enough that boy bands are back with a vengeance, these are the sort of lyrics that they're giving us:

But, no, a subtly nefarious judgment does creep in, in the chorus:

So, that insecurity that they were complaining about in the opening line? That wasn't actually a complaint. It was actually a precondition for finding her desirable. And confidence? Well, if she should have it, it's clear that it should only come from the affirmation that the singer offers. And, by extension, that a girl's confidence only ever comes from guys. Which means that girls who are already confident and self-aware - the kind who wear make-up? Well, they must have gained that "knowledge" from other boys, and this, of course, means that they're not innocent and not actually beautiful.

One last bit on the logic of beauty, according to One Direction. Hilariously/disturbingly, the lyric holds that a girl can never actually know that she, herself, is beautiful. If unawareness of one's beauty is what makes them beautiful, then someone who is aware of their beauty would, ironically, no longer be beautiful. The only options are ignorance and self-deception. Super.

[These lyrics also reminded me of a story about a male high school student near Toronto who was suspended for distributing a letter that celebrated girls' "inner-beauty". Which he did, unfortunately, by not-so-subtly excluding the girls who "dress in revealing clothing". Who, clearly, couldn't possibly possess inner-beauty.]

You're insecureThis is from One Direction's "What Makes You Beautiful", by the way. And this opening verse seems pretty innocuous, as if they're saying that the "you" should be more confident. Even the part about not needing make-up isn't necessarily judgmental, and could actually be a compliment that isn't saying anything specifically about make-up or what it signifies.

Don't know what for

You're turning heads when you walk through the door

Don't need make-up

To cover up

Being the way that you are is enough

Everyone else in the room can see it

Everyone else but you

But, no, a subtly nefarious judgment does creep in, in the chorus:

If only you saw what I can seeBecause, as it turns out, the girl is beautiful precisely because she doesn't know that she's beautiful. That's the catch, and that's what makes those seemingly harmless lines about make-up a great deal more loaded than they first appear. A girl who doesn't wear make-up is, presumably, unaware and ignorant of her sexuality (ie. she's still pure and innocent) while one who does is comparatively world-weary and, ostensibly, has been around the block a few times.

You'll understand why I want you so desperately

Right now I'm looking at you and I can't believe

You don't know

Oh oh

You don't know you're beautiful

Oh oh

That what makes you beautiful

So, that insecurity that they were complaining about in the opening line? That wasn't actually a complaint. It was actually a precondition for finding her desirable. And confidence? Well, if she should have it, it's clear that it should only come from the affirmation that the singer offers. And, by extension, that a girl's confidence only ever comes from guys. Which means that girls who are already confident and self-aware - the kind who wear make-up? Well, they must have gained that "knowledge" from other boys, and this, of course, means that they're not innocent and not actually beautiful.

One last bit on the logic of beauty, according to One Direction. Hilariously/disturbingly, the lyric holds that a girl can never actually know that she, herself, is beautiful. If unawareness of one's beauty is what makes them beautiful, then someone who is aware of their beauty would, ironically, no longer be beautiful. The only options are ignorance and self-deception. Super.

[These lyrics also reminded me of a story about a male high school student near Toronto who was suspended for distributing a letter that celebrated girls' "inner-beauty". Which he did, unfortunately, by not-so-subtly excluding the girls who "dress in revealing clothing". Who, clearly, couldn't possibly possess inner-beauty.]

Friday, September 30, 2011

It had to happen: Sagan vs. Snooki

So, this appeared in my Facebook newsfeed, yesterday. Apparently, I should be congratulated:

I recognized Snooki in an instant; I know who Carl Sagan is, in a vague sense, but I can't say that I had any idea what he looked like. So, good for me - I am, apparently, what's wrong with the world. Here are all of the other responses to the picture, again from Facebook:

(An important note: this was posted on the Fb page of a graduate student, and likely responded to by other graduate students. I don't know whether this means that they would be inclined to be disingenuous about knowing who Snooki is - that is, I don't know if they would lie in order to save face - but I wouldn't be surprised if these people are actually intellectual clichés of the I-don't-even-own-a-TV variety.)

Now, I get the joke. Carl Sagan could be any intellectual who is/was on TV and the point would be the same - people care more about vacuous celebutantes and reality stars than they do about substantive stuff, like how the universe works. Point taken.

But... for the purposes of this illustration, it's Carl Sagan and not Steven Hawking or, especially for us Canadians, David Suzuki. And that annoys me for a few reasons:

I recognized Snooki in an instant; I know who Carl Sagan is, in a vague sense, but I can't say that I had any idea what he looked like. So, good for me - I am, apparently, what's wrong with the world. Here are all of the other responses to the picture, again from Facebook:

- I know I've seen that guy before, but have no idea who the woman is.

- Carl Sagan! Do I get "billions and billions" of Science Points for that? And no, I don't know who the other one is.

- I don't know Snooki enough to recognize her on sight, so until reading these comments I had no idea who either person was.

- Val is happy to report that still she has no idea who either of these people are

- i can spot sagan at 500 paces... who is snooki?

(An important note: this was posted on the Fb page of a graduate student, and likely responded to by other graduate students. I don't know whether this means that they would be inclined to be disingenuous about knowing who Snooki is - that is, I don't know if they would lie in order to save face - but I wouldn't be surprised if these people are actually intellectual clichés of the I-don't-even-own-a-TV variety.)

Now, I get the joke. Carl Sagan could be any intellectual who is/was on TV and the point would be the same - people care more about vacuous celebutantes and reality stars than they do about substantive stuff, like how the universe works. Point taken.

But... for the purposes of this illustration, it's Carl Sagan and not Steven Hawking or, especially for us Canadians, David Suzuki. And that annoys me for a few reasons:

- Awareness of Snooki's existence does not necessarily make one a fan of her or of her show. Collapsing those two things into one-and-the-same makes no sense.

- Carl Sagan has been dead for 15 years, and his TV show first aired more than 30 years ago; that someone might not know what he looks like is probably not surprising. (Granted, his show's been aired many times since then. But, to use but one example, Seinfeld, which ended in the late 90s, is aired constantly in syndication - and despite that, it's usually the case that none of my 18-21 year-old students have ever watched it. Which brings me to a related point...)

- The comparison is ridiculously ageist. Because the Sagan reference is so dated, the person who put the image together must have known that virtually everyone under the age of 20 (if not 30) will have no clue who he is. So this isn't so much directed at the ignorant and intellectually-stunted - which is what the image implies - as it is at the young. (The choice of a smart dude and dumb woman also feels just a bit sexist.)