Yesterday, Michael Sam, a college football player who intends to enter the NFL draft in May, told Sports Illustrated that he's gay. It's being described as "outing", but Sam's sexuality was no surprise to his college team, whom he informed in August, and apparently "only two or three [NFL teams] didn't know" beforehand.

Now, the fact that this is news - that Sam would be the first out player in the history of the NFL - is obviously indicative of heterosexism. That all of the coaches, scouts, and such interviewed by Sports Illustrated confirmed that this would be a problem, that it would be a distraction to the team and hurt his own prospects is also unsurprising, and also an explicit admission of widespread homophobia. But these are not surprising findings in North American sports, even if they're still upsetting.

As recently as a year ago, baseball's Torii Hunter was saying that having a gay teammate would be "difficult and uncomfortable", and the comment - while widely criticized by media-types - was basically a non-issue among people who are actively involved in the sport. Or in all of North America's big four sports, for that matter. The NBA's Jason Collins, a mediocre player nearing the end of his career, came out in spring 2013 and has been unable to find any more work. The NFL's Chris Kluwe, considered more-or-less average among punters, became an outspoken advocate of gay marriage and critic of its enemies and he, too, has been unable to find a job.

That the NBA's only out gay player and pro sports' most vocal straight ally find themselves unemployed is not evidence of a conspiracy, but it's reflective of this fact, at the very least - homophobia is deeply entrenched in the culture of sport.

What makes things more interesting for Sam, though, is that he's not on the verge of retirement, (like Collins) nor does he play a relatively marginal position that's rather easy to replace (like Kluwe). Rather, Sam is the SEC Defensive Player of the Year - not just the best at his own position, but judged the very best among all players on defense among the 14 team, Division I Southeastern Conference.

So, if Sam is going to be punished for his admission, it might be useful to look at how former Defensive Players of the Year have been treated by the NFL draft:

2012 - Round 1, Pick 17 - Jarvis Jones, Linebacker

2011 - Round 1, Pick 6 - Morris Claiborne, Cornerback

2010 - Round 1, Pick 5 - Patrick Peterson, CB

2009 - Round 1, Pick 8 - Rolando McClain, LB

2008 - Round 1, Pick 5 - Eric Berry, Safety

2007 - Round 1, Pick 5 - Glenn Dorsey, Nose Tackle

2006 - Round 1, Pick 11 - Patrick Willis, LB

2005 - Round 2, Pick 33 - Demeco Ryans, LB

2004 - Round 1, Pick 17 - David Pollack, LB

2003 - Round 5, Pick 142 - Chad Lavalais, Defensive Tackle

(previous to 2003, a single Player of the Year was named, which included offense and special teams)

Even with the inclusion of 2003's outlier, that's an average of 25th pick. And Sam? The various sources I've looked at were guessing, even before the public announcement, he could go anywhere from 3rd to 7th round - the vicinity of Lavalais, the outlier, rather than the norm. Following the announcement, the consensus seems to be that he'll go even lower. That is, if he's drafted at all.

Now, Sam is considered small for his position, (he's 6'2", while DEs tend to fall in the 6'3"-7" range) which is a criticism that unavoidably, and reasonably, damages his draft value. Doug Flutie, notably, won the Heisman Trophy and was named the best player in college football, only to be drafted in the 11 round and 285th overall. So, these things matter, and it's entirely possible that he'd fall outside the first round, controversy or no. But now we're suggesting that he would likely be the lowest-drafted SEC Defensive Player of the Year, ever? That he could, conceivably, go undrafted unless a team with "a strong owner, savvy general manager and veteran coach" can "make [it] work"? (We could spend hours peeling back the layers of the language that executives have used to describe Sam. Likewise, in discussing how cowardly it is that they've all hidden behind anonymity.)

This makes it sound like we're talking about someone who is intentionally divisive, who makes his sexuality central to his public persona. You'd think we were talking about someone who wears political messages on the field, who makes controversial remarks to media, who very openly and often talks about his sexuality, and whose media profile creates a conscious "distraction." Someone like, say, Tim Tebow.

And for what it's worth? Even with that baggage and similar concerns that his game wouldn't translate to the NFL, Tebow was picked 25th.

Showing posts with label sports. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sports. Show all posts

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

Tuesday, January 07, 2014

If you're gonna name your team after real people, at least do it right

We live in a world with NFL teams like the Washingtons* and MLB teams like the Clevelands*, that celebrate a tradition of white settler racism. A world where most sports fans lie somewhere on a spectrum from oblivious to indignant, mascots are unrepentantly racist, and owners have dug in their heels in defense of horribly offensive "traditions".

[* That's right. I refuse to use their chosen names. More on that below.]

That being the case, it seems important to celebrate the teams that do it right. Teams like the Spokane Indians. From Rodney Harwood of the Indian Country Today Media Network:

A Salish-language logo? And it's also their primary logo? That's pretty damn cool. It also addresses the obvious concern that this is a team called "the Indians". This is a word that was applied to the Aboriginal people of North America by white settlers, who misidentified them as Asian - and then didn't bother to correct themselves. It's inherently racist.

Impressively, the team is aware of this and shares those concerns - they don't use mascots, they don't have chants, none of that cartoonish crap that the Washingtons or Clevelands use. Says team co-owner Andy Billig, “We have a very positive relationship with the local tribes. We would talk with them from time-to-time to check in and say, ‘How are we doing?’ Even if we weren’t using any imagery, the name of the team was still the Spokane Indians and we knew that could potentially be sensitive. We believe that we are still the only professional sports team to collaborate with local tribes in this way.”

The difference, with this Spokane team, is all in the collaboration and the new/old language. In making the Salish name the one that goes on their logo, with the help of the Spokane Nation, the name is effectively reclaimed - "Indians" becomes, at best, an English translation of the actual name. And an officially sanctioned nickname for the specific people that they represent. And it will surely decline in use as people familiarize themselves with the pronunciation of the Salish name.

This, by the way, is what that logo looks like:

In the past, I've always come down squarely against every iteration of the people-as-team-mascot kind of sports team. But this one, one that Spokane elders themselves say shows them respect and bring them pride? This is one that I feel pretty good about.

[* That's right. I refuse to use their chosen names. More on that below.]

That being the case, it seems important to celebrate the teams that do it right. Teams like the Spokane Indians. From Rodney Harwood of the Indian Country Today Media Network:

"In 2006, the baseball team’s front office and the tribe collaborated to come up with a team logo not only saying Spokane Indians in English, but developed a team logo printed in the Salish language, which was depicted on the sleeve of its uniforms.

"The Spokane Indians baseball team will take that collaboration one step further, making the logo in the Salish language the main logo on the front of its home uniforms for the 2014 season."

A Salish-language logo? And it's also their primary logo? That's pretty damn cool. It also addresses the obvious concern that this is a team called "the Indians". This is a word that was applied to the Aboriginal people of North America by white settlers, who misidentified them as Asian - and then didn't bother to correct themselves. It's inherently racist.

Impressively, the team is aware of this and shares those concerns - they don't use mascots, they don't have chants, none of that cartoonish crap that the Washingtons or Clevelands use. Says team co-owner Andy Billig, “We have a very positive relationship with the local tribes. We would talk with them from time-to-time to check in and say, ‘How are we doing?’ Even if we weren’t using any imagery, the name of the team was still the Spokane Indians and we knew that could potentially be sensitive. We believe that we are still the only professional sports team to collaborate with local tribes in this way.”

The difference, with this Spokane team, is all in the collaboration and the new/old language. In making the Salish name the one that goes on their logo, with the help of the Spokane Nation, the name is effectively reclaimed - "Indians" becomes, at best, an English translation of the actual name. And an officially sanctioned nickname for the specific people that they represent. And it will surely decline in use as people familiarize themselves with the pronunciation of the Salish name.

This, by the way, is what that logo looks like:

In the past, I've always come down squarely against every iteration of the people-as-team-mascot kind of sports team. But this one, one that Spokane elders themselves say shows them respect and bring them pride? This is one that I feel pretty good about.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Fluffy sports post for the end of the year

One of the reasons that I love sports is that I also love a good story. Unfortunately, sports commentary and writing is filled with awful storytelling. And rather than say anything substantive about sports writing, I'll use this as an excuse to post my two favorite jokes about it. Happy new year!

|

| From xkcd.com |

Monday, November 11, 2013

What would happen if baseball writers voted the way they claimed to vote?

This is a comment from a reader of Joe Posnanski's blog, though it could come from any number of sports writers and "traditionalist" fans:

While a player on a losing team certainly can be MVP, that is a black mark on that player’s record. The point is to win games. While the Angels certainly won more games this year because they had Mike Trout, that value is diminished because the Angels were so bad. A lot of that is beyond Trout’s control, and certainly the play of the rest of the team does not diminish his contribution, it does diminish that contribution’s value. If Trout plays for the Astros is he MVP? If Miguel Cabrera’s performance is slightly below Trout’s, but he helps push the Tigers into the playoffs, isn’t that more valuable?

So, now that you've considered the situation as a hypothetical, I can fill-in the specifics that were probably obvious to everyone who's a baseball fan. Excellent Player and Mediocre Team are Mike Trout and the Angels, while Incredible Player and Good Team are Miguel Cabrera and the Tigers.

Now, I'm copy-and-pasting this not to rehash the same discussion that happens every year, among everyone who writes about baseball. Because that would be really, really tedious. Instead, I want to a somewhat different approach.

The logic expressed in that quote goes something like this: you can't be MVP unless your team made the playoffs. Rather than argue the point, I'm going to accept it. Because, hey, your criteria is your own. You want to constraint the meaning of "value" such that it can only refer to players on playoff teams? Sure.

Here's the thing, though. Whatever definition you use, you have to be totally consistent in its application. Display some integrity. Establish your criteria, and then follow it.

That doesn't sound all that hard, does it? The thing is, in practice, the folks who add this playoff stipulation are rarely consistent. Writes baseball blogger Murray Chass,

When I voted for m.v.p., I didn’t look for any definitions because there aren’t any. Each voter has the freedom to decide for himself what “most valuable” means. To me, it means the player without whom his team couldn’t have done what it did. I always felt that the greater number of outstanding players a team had the less valuable each of those players was.

If I were voting this year, I’d find it hard to ignore Cabrera. He led the league in batting, on-base and slugging percentages, the combination of the two and batting with runners in scoring position. He was second in home runs, total bases and runs batted in, tied for second in runs scored and third in hits and walks. And don’t forget, he led his team to a division title. Would the Tigers have won it without him? No.

Chass' first criteria is that the "team couldn't have done what it did" without that player. It's badly expressed, but I take that to mean "a player without whom the team wouldn't have made the playoffs". That seems more or less confirmed by his subsequent argument in favor of Miguel Cabrera. And, sure, his selection of Cabrera for American League MVP totally fits with that logic. The Tigers won the division by a single game, and Cabrera was inarguably the best player on the team. Good job.

But there's a problem, and it arises when Chass starts talking about the other league's MVP:

In this instance, I think I would be tempted to vote for Goldschmidt, but the only race his team, Arizona, was involved in after June was a race for .500. With McCutchen providing the spark, Pittsburgh was in the division race to the end and maintained its wild-card lead.

Say, what? Inexplicably, right after explaining his criteria, Chass does the exact opposite of what he said he would do. Yowza. (Unless he sincerely meant that he could define "did what they did" in totally arbitrary ways, like "finish around .500". Which I can't believe he actually meant.)

Now, obviously, human beings often don't make sense. They set one standard, then vote according to another. This probably shouldn't be surprising, but it'd be nice if these voters - who are paid to do work like this, even if only indirectly, because a) they get to vote because they're sports writers, and b) they subsequently get to write about this news, which they themselves have made - were consistent in some way, right? And if they were, what would actually happen? Well, let's play pretend.

First, any NL MVP discussion would have to immediately exclude players from non-playoff teams. Legitimate MVP contenders from non-playoff teams, guys like Paul Goldschmidt, Carlos Gomez, or Troy Tulowitzki? Sorry, Chass, they're all out.

Second, and maybe more controversially, you also have to exclude every player who comes from a team that would have won their division/wildcard without that player. Atlanta and LA, for example, both won their divisions by ten or more games - no single player comes close to making an individual contribution that could account for that gap, so Clayton Kershaw and Freddie Freeman (among others) are also out. Kershaw's a favorite for MVP, so that one especially hurts.

Following this logic, then, an AL MVP ballot looks something like this: Cabrera, Donaldson, Scherzer, Sanchez, Longoria, Ellsbury, Victorino, Zobrist, Beltre, Verlander. (The arrangement might vary, but the players should be largely the same.)

You might notice a few auspicious absences. Dustin Pedroia, like Kershaw, is excluded not because he's not one of the ten best, but because the Sox probably make the playoffs without him. So, not an MVP candidate. Trout, Robinson Cano, Chris Davis, and Felix Hernandez are all disqualified because their teams miss the playoffs with or without him. No one actually wants to see a ballot like that - you're excluding way too many of the league's best player - but that's the price of being consistent, right? Right. Good work, everyone.

The odds that we'll ever see a ballot like that, though? Well, it's not zero. But it's somewhere close to it.

Because here's the thing. The guys like Chass, who say that you should need to be on a playoff team? Mike Trout is probably their second or third choice. Davis is somewhere in their top five, too. And Cano isn't far behind. I don't even have to ask Chass and company if I'm right about this - I know I am. And these guys should be up for consideration, because they deserve it.

TL;DR: No one who espouses that whole valuable=playoffs thing actually adheres to it, because it would produce terrible results. And from that I can only conclude that they don't actually believe it, either.

Thursday, February 28, 2013

The Saginaw Chippewa and People-as-Mascots: there's a Santayana joke in here, somewhere

A while back, this interview showed up on my Twitter feed, about the stance of the Saginaw Chippewa tribe with respect to sports teams that use Aboriginal names and likenesses as logos and mascots. In short, they're supportive of these symbols provided that they aren't used mockingly and serve to educate, and teams like the Western Warriors (a high school basketball team) and Central Michigan Chippewas (a College team) have their full support.

Just in case you're a TL;DR kind of reader: folks on Twitter claimed that the above interview might lead some to re-think their position on such mascots. But it shouldn't. And that's what this particular blog is about.

I have some strong feelings on this topic - which I've shared before - but I'm not entirely opposed to the sentiment that's expressed in the article. Education is certainly a good thing, and if a mascot can actually increase historical awareness, that would be pretty awesome.

The problem is, I don't think it can, or at least it hardly ever does. And for an argument that's premised on historical awareness, there's at lease this one little bit of unfortunate irony, offered by Frank Cloutier, public relations director for the Saginaw Chippewa:

Now, I could take the easy path, here, and argue that "Brave" and "Indian" certainly can be derogatory but I won't. That's less an irony than it is a disagreement. Instead, I'm going to take a closer look at the "Redskin" team that he's referring to. (It's oblique, in this instance, but he later says that it would be "most appropriate" if the Washington Redskins changed their name.)

The irony, instead, that the football team's logo and mascot might exist, and have persisted, precisely because an earlier Aboriginal leader advocated for it. From a 2002 Washington Post article that's since gone offline:

For all that emphasis on history and education, Cloutier has ignored the very history of racist logos - and how that Redskins name and logo that he finds distasteful is, itself, a product of compromise and collaboration between white owners and a Native-American leader. Clearly, what's worth celebrating, and the value or meaning of educating, is highly relative. What strikes Cloutier as offensive is perfectly acceptable to Wetzel. And, presumably, Wetzel had his own line-in-the-sand, marking the division between the Redskins and the space where unacceptable mascots and logos lay.

For what it's worth, I'm in agreement with Cloutier with respect to the Redskins - the mascot should go, the logo should go, the name should go. But I'm not on-board with his argument that the names and logos are okay provided they're well-intentioned and have some educational component. Intentions don't speak all that well to the large contingent of fans who don't respect the culture, and education doesn't mesh particularly well with the ethos of organized sports. (If sport and critical thought tended to accompany one another, we wouldn't have to have conversations like 'is this racist?' all the time.)

And if history has taught us anything, it's that, eventually, another Frank Cloutier will come along and suggest that the Western Warriors and Central Michigan Chippewas are just bad as the Washington Redskins.

Just in case you're a TL;DR kind of reader: folks on Twitter claimed that the above interview might lead some to re-think their position on such mascots. But it shouldn't. And that's what this particular blog is about.

I have some strong feelings on this topic - which I've shared before - but I'm not entirely opposed to the sentiment that's expressed in the article. Education is certainly a good thing, and if a mascot can actually increase historical awareness, that would be pretty awesome.

The problem is, I don't think it can, or at least it hardly ever does. And for an argument that's premised on historical awareness, there's at lease this one little bit of unfortunate irony, offered by Frank Cloutier, public relations director for the Saginaw Chippewa:

Our position is that if it's not derogatory and it's being used appropriately, with an opportunity to share or cross-share our culture, then it's fine. There's nothing derogatory about "Warriors" or "Braves." There's nothing derogatory about "Indian." But terms like "Redskin" or "Half-Breed," those are derogatory terms to us.

Now, I could take the easy path, here, and argue that "Brave" and "Indian" certainly can be derogatory but I won't. That's less an irony than it is a disagreement. Instead, I'm going to take a closer look at the "Redskin" team that he's referring to. (It's oblique, in this instance, but he later says that it would be "most appropriate" if the Washington Redskins changed their name.)

The irony, instead, that the football team's logo and mascot might exist, and have persisted, precisely because an earlier Aboriginal leader advocated for it. From a 2002 Washington Post article that's since gone offline:

“I said, ‘I’d like to see an Indian on your helmets,’ “ which then sported a big “R” as the team logo, remembers [former chairman of the Blackfoot tribe and president of the National Congress of American Indians Walter] Wetzel, now 86 and retired in Montana. Within weeks, the Redskins had a new logo, a composite Indian taken from the features in Wetzel’s pictures. “It made us all so proud to have an Indian on a big-time team. . . . It’s only a small group of radicals who oppose those names. Indians are proud of Indians.”

For all that emphasis on history and education, Cloutier has ignored the very history of racist logos - and how that Redskins name and logo that he finds distasteful is, itself, a product of compromise and collaboration between white owners and a Native-American leader. Clearly, what's worth celebrating, and the value or meaning of educating, is highly relative. What strikes Cloutier as offensive is perfectly acceptable to Wetzel. And, presumably, Wetzel had his own line-in-the-sand, marking the division between the Redskins and the space where unacceptable mascots and logos lay.

For what it's worth, I'm in agreement with Cloutier with respect to the Redskins - the mascot should go, the logo should go, the name should go. But I'm not on-board with his argument that the names and logos are okay provided they're well-intentioned and have some educational component. Intentions don't speak all that well to the large contingent of fans who don't respect the culture, and education doesn't mesh particularly well with the ethos of organized sports. (If sport and critical thought tended to accompany one another, we wouldn't have to have conversations like 'is this racist?' all the time.)

And if history has taught us anything, it's that, eventually, another Frank Cloutier will come along and suggest that the Western Warriors and Central Michigan Chippewas are just bad as the Washington Redskins.

Thursday, February 21, 2013

Some depressing notes on cultural representation: Reeva Steenkamp and Oscar Pistorius

If you're paying any attention at all to the murder of Reeva Steenkamp, you've probably seen these tabloid covers before. They're everywhere. (As is the still-developing story and trial, which I won't get into here... I assume that you have the Google.) But I wanted to a) have a copy of them where I could easily find them, because they'll certainly be worth talking about even years from now, and b) add a couple of my own comments.

If you haven't seen the covers, but you're familiar with the story more generally, I should probably warn you - the images are almost unbelievably tasteless:

Ugh. Here are some observations:

If you haven't seen the covers, but you're familiar with the story more generally, I should probably warn you - the images are almost unbelievably tasteless:

Ugh. Here are some observations:

- It's depressing, if unsurprising, that both papers chose to focus so totally on Steenkamp's mostly naked body, her name appearing in tiny print that's easily missed.

- The Daily News one-ups the New York Post with their picture. While the Post's pose is a bit generic and Steenkamp's smile looks largely indifferent, the News uses a picture that's clearly been designed to, well, arouse. Most notably, Steenkamp is holding a melting ice cream cone, which is a hideously unsubtle allusion to ejaculation. It would be cheesy, if it weren't so sleazy.

- One cover identifies her simply as "blonde" and the other as a "model", which, while true, also marginalizes the work - more important work, arguably - that she had been doing most recently as an aspiring lawyer and activist who spoke about violence against women. Reducing someone to their profession is hardly new, especially in headlines, but there's something particularly disrespectful about it - especially "blonde" - in this case. Both identify her as Pistorius' "gal pal", which seems unnecessarily cheeky and seems to minimize the seriousness of their relationship. (That is, it feels like very subtle slut-shaming.)

- Equally interesting, both covers identify Oscar Pistorius by name only in the small print. One calls him "Blade" (as in Blade Runner, his nickname) and the other "Blade Gunner" (a play on the nickname), and both also refer to him as the "Legless Olympian". Again, not new or surprising, though there's something additionally awful about these identifiers, too. The "Blade" references seem designed to hint at violence - it feels aggressive and menacing - which is not at all how the name is intended to be interpreted, since the blades are literally his prostheses. The legless Olympian bit is also exaggerated, if not quite so twisted: Pistorius has legs, after all, though they are partially flesh-and-bone and partially prosthetic. That is, he's not actually legless.

- The need to vilify Pistorius by way of his disability - and I'm not saying he shouldn't be vilified, just commenting on how I see it being done - is also telling. Disability scholars have commented on how Pistorius has been built-up, to this point, as some sort of "super-crip" or as "inspiration porn". As a disabled man who was able to compete against able-bodied runners in the Olympics, he inadvertently serves a couple of normative cultural functions. For instance, he confirms that everyone should aspire to a particular standard of able-bodiedness, while also appearing to demonstrate that this standard is available to everyone if they try hard enough. (It may not go without saying: these attitudes are dangerous and simply wrong, both of them.) But since he's now an accused-murderer, the media have to distance him from that inspiration function - and how better to do that than be recasting his unrelenting push against the social and physical boundaries of disability as, in fact, a nefarious character-flaw that somehow contributed to his need to murder a blonde model and gal pal? This is where that slippage between the blades of his legs and the blades of some implied murder weapon (the cricket bat that he used to break open the bathroom door?) seems particularly meaningful and not simply clever.

- And this logic of equating disability with violence is hardly unique to the tabloids. The Toronto Star's never-classy Rosie DiManno makes an even more explicit connection, describing Pistorius in terms of "the musky whiff of danger, a risk-flirt, testosterone-propelled dash and flash, as if constantly defying the limitations imposed by a body with limbs missing because limitations were what Pistorius adamantly rejected." DiManno suggests, somehow, that the "restless and recklessness" with which Pistorius approached his disability and sport somehow makes it unsurprising that he could kill someone. If that's true, then we should probably begin to suspect that every non-normative body contains a homicidal maniac, and every ambitious person is capable of murder. Or maybe DiManno thinks this is only true of people who are both ambitious and non-normative, who won't simply accept definitions of normal that exclude them. Maniacs, clearly, all of them.

Thursday, January 03, 2013

The sad case of Ryan Freel, and what players like Brett Lawrie should learn from it

When I wrote about the Toronto Blue Jays' Brett Lawrie last summer - suggesting that, in cases like his, 'playing hard' could easily be a bad thing - I compared him to Eric Byrnes, a late-peaking player who burned bright for a few years (the 67th most valuable hitter from 2004-2007) before suddenly fizzling. But I might have just as easily compared Lawrie to Ryan Freel.

The 36 year-old Freel, who hadn't played Major League Baseball since 2009, died last week, after shooting himself in the head. According to his family, baseball-related concussions - he suffered somewhere between 10 and 20 of them - were almost certainly to blame. According to his ex-wife,

I've actually known about Ryan Freel since he debuted, given that he came up with the Blue Jays in 2001. It's a somewhat vague memory, at this point, but I remember really liking him - he was small and overly serious. He was also quite good, and Freel's career and performance (the 62nd most valuable hitter from 2004-2006) was shockingly similar to that of Byrnes. And, like Byrnes, a lot of that value came from doing the little things that aren't easily appreciated - running the bases well, stealing bases, playing strong defense.

Freel was not highly-valued or considered to be incredibly talented (unlike Lawrie, in this regard) but was considered hard-nosed and gutsy, sacrificing his body at every turn and chasing after every ball within a couple hundred feet of him. And, like Byrnes, in his early 30s he quickly went from being a tremendously useful, and above-average, everyday player to a poor-hitting scrub. Again, like Byrnes, the injuries eventually became too much to play through, too much of an impediment and detriment.

Freel and Byrne were only useful so long as they could run hard and crash hard - be it into walls, into the stands, into opposing players, or even, occasionally, their own teammates. (A collision with a teammate is often cited as the concussion that finally ended Freel's career.) And when they could no longer do those things, their below-average skills couldn't keep them employed.

Lawrie is a better athlete, and probably a better player, than either Freel or Byrne. But one would hope that players like these can take something away from Freel's story.

The 36 year-old Freel, who hadn't played Major League Baseball since 2009, died last week, after shooting himself in the head. According to his family, baseball-related concussions - he suffered somewhere between 10 and 20 of them - were almost certainly to blame. According to his ex-wife,

“I don’t know how many times he would talk about sliding into second or third base and blacking out or seeing stars. I cringed that that’s who he was – all-out, full throttle. It was very hard to watch.”

I've actually known about Ryan Freel since he debuted, given that he came up with the Blue Jays in 2001. It's a somewhat vague memory, at this point, but I remember really liking him - he was small and overly serious. He was also quite good, and Freel's career and performance (the 62nd most valuable hitter from 2004-2006) was shockingly similar to that of Byrnes. And, like Byrnes, a lot of that value came from doing the little things that aren't easily appreciated - running the bases well, stealing bases, playing strong defense.

Freel was not highly-valued or considered to be incredibly talented (unlike Lawrie, in this regard) but was considered hard-nosed and gutsy, sacrificing his body at every turn and chasing after every ball within a couple hundred feet of him. And, like Byrnes, in his early 30s he quickly went from being a tremendously useful, and above-average, everyday player to a poor-hitting scrub. Again, like Byrnes, the injuries eventually became too much to play through, too much of an impediment and detriment.

Freel and Byrne were only useful so long as they could run hard and crash hard - be it into walls, into the stands, into opposing players, or even, occasionally, their own teammates. (A collision with a teammate is often cited as the concussion that finally ended Freel's career.) And when they could no longer do those things, their below-average skills couldn't keep them employed.

Lawrie is a better athlete, and probably a better player, than either Freel or Byrne. But one would hope that players like these can take something away from Freel's story.

Wednesday, November 21, 2012

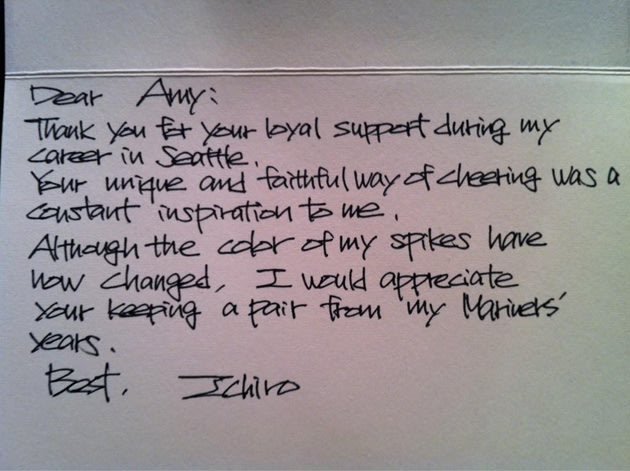

Baseball follow-up: and sometimes, it's all love

I blogged yesterday about the ambivalence that I feel for pro sports. But today, I read a story that reminds me that, sometimes, I don't have to feel ambivalent. Sometimes, it's all good.

This is Ichiro, inarguably one of the world's most famous ballplayers:

For the first ten years of his career, he was also one of the world's best ballplayers - he collected the 4th-most Wins Above Replacement from 2001-10, during which he also broke the record for hits in a single-season.

Just as importantly, he's earned a reputation for being a really nice guy. How nice? This is the letter that he wrote to a fan in Seattle, how kept a running tally of how many hits Ichiro recorded every season on her Ichimeter: (apologies to Yahoo for so shamelessly stealing their image and story)

And, sure enough, Ichiro included a pair of shoes and a bat, all autographed. Pretty awesome stuff.

This is Ichiro, inarguably one of the world's most famous ballplayers:

For the first ten years of his career, he was also one of the world's best ballplayers - he collected the 4th-most Wins Above Replacement from 2001-10, during which he also broke the record for hits in a single-season.

Just as importantly, he's earned a reputation for being a really nice guy. How nice? This is the letter that he wrote to a fan in Seattle, how kept a running tally of how many hits Ichiro recorded every season on her Ichimeter: (apologies to Yahoo for so shamelessly stealing their image and story)

And, sure enough, Ichiro included a pair of shoes and a bat, all autographed. Pretty awesome stuff.

Monday, November 19, 2012

Love, hate, and baseball

Last week, the Toronto Blue Jays - the only sports team that has earned entirely uncritical, and unrepentant, love from me - made an insanely aggressive trade. It's not an exaggeration to say that it's probably the most exciting move that the team has made since they signed Roger Clemens, if not Rickey Henderson. And the latter happened almost 20 years ago.

But just as the trade reminds me why I love sports, it's equally capable of reminding me why I hate sports.

The Miami Marlins, with whom the Jays completed the trade, have now divested themselves of the large majority of their payroll. Last season, they started the year with (if I'm remembering correctly) ten players making over $2m, several of whom were also making north of $10m. Now, they have two, the highest-paid player making "only" $6m. In total, their payroll is now hovering somewhere around $20m.

So, why is this hate-worthy? Because the Marlins are infamous for exploiting baseball's revenue-sharing system. Designed to help poorer franchises compete with the likes of the Yankees and Red Sox, teams like the Marlins instead use the money to increase their profit. From 2002 to 2010 - that is, since current owner Jeffrey Loria bought the team - the perennially-cheap Marlins averaged a total player payroll of about $55m and a pre-sharing profit of something like $15m. After revenue sharing? Most like $45m - or about 80% of their total player costs. That's not a sports team that's being run out there to actually win. That's a team that's designed to lose, and, perversely*, make money doing it.

And a year after appearing to reverse course and doing badly - having to reverse course, because they had convinced the city and its politicians that they would build a good team if the public built them a $600m stadium - the Marlins have decided to return to the reliably profitable method of tanking on the cheap. And, honestly, who can blame them? There's a lot of chance and random variation that gets in the way of turning a profit with a winning-team; but there's a formula that guarantees monetary success if you do badly enough. Given those options, it's not surprising that one or more teams would take the good-for-business, bad-for-baseball approach. It makes more than a little bit of sense.

But, fuck, it really makes me hate pro baseball.

*I say "perversely" as if capitalism doesn't routinely reward failure. It does, of course. But it's still a fair description.

But just as the trade reminds me why I love sports, it's equally capable of reminding me why I hate sports.

The Miami Marlins, with whom the Jays completed the trade, have now divested themselves of the large majority of their payroll. Last season, they started the year with (if I'm remembering correctly) ten players making over $2m, several of whom were also making north of $10m. Now, they have two, the highest-paid player making "only" $6m. In total, their payroll is now hovering somewhere around $20m.

So, why is this hate-worthy? Because the Marlins are infamous for exploiting baseball's revenue-sharing system. Designed to help poorer franchises compete with the likes of the Yankees and Red Sox, teams like the Marlins instead use the money to increase their profit. From 2002 to 2010 - that is, since current owner Jeffrey Loria bought the team - the perennially-cheap Marlins averaged a total player payroll of about $55m and a pre-sharing profit of something like $15m. After revenue sharing? Most like $45m - or about 80% of their total player costs. That's not a sports team that's being run out there to actually win. That's a team that's designed to lose, and, perversely*, make money doing it.

And a year after appearing to reverse course and doing badly - having to reverse course, because they had convinced the city and its politicians that they would build a good team if the public built them a $600m stadium - the Marlins have decided to return to the reliably profitable method of tanking on the cheap. And, honestly, who can blame them? There's a lot of chance and random variation that gets in the way of turning a profit with a winning-team; but there's a formula that guarantees monetary success if you do badly enough. Given those options, it's not surprising that one or more teams would take the good-for-business, bad-for-baseball approach. It makes more than a little bit of sense.

But, fuck, it really makes me hate pro baseball.

*I say "perversely" as if capitalism doesn't routinely reward failure. It does, of course. But it's still a fair description.

Monday, November 12, 2012

Miguel Cabrera didn't win the Triple Crown

1.

In the NHL's 2010-2011 season, Daniel Sedin - a player in the Western Conference - led the league with 104 points and won the Art Ross Trophy as the leading scorer. The Eastern Conference's Martin St. Louis scored 99 points, second-best in the NHL, and was awarded nothing. Corey Perry - another Western Conference player - led the league with 50 goals and was awarded the Maurice Richard Trophy as top goal-scorer. Martin St. Louis's teammate, Steven Stamkos, scored 45 to lead the Eastern Conference, but nobody noticed or cared.

2.

One of the oft-repeated arguments in favor of pitcher Jack Morris's election to the baseball Hall of Fame is that he led baseball in Pitcher Wins during the 1980s, with 162, and every other pitcher who led a particular decade in Pitcher Wins is in the Hall of Fame. Let's ignore, for the moment, that this is actually a pretty meaningless stat - that Pitcher Wins are heavily dependent on the quality of the pitcher's team, as well as dependent on having a lot of opportunities to start, and that we have much better stats available - and see whether that's actually true.

From 1977-1986 - a full decade - Ron Guidry led baseball with 163 Pitcher Wins. (Morris had 144 over the same time-frame.) Ron Guidry is not in the Hall of Fame. From 1984-1993, Frank Viola and Roger Clemens tied for the most Pitcher Wins, again with 1963. Frank Viola is also not in the Hall of Fame, and Clemens will be hard-pressed to shake the steroid-user label and qualify for the Hall, at least for the first few years.

So, even if I limit myself to the years where Morris was also active, it's pretty clear that the argument falls apart unless it's hilariously constrained. It's all about the easy and ready-made reference points, apparently.

3.

Rogers Hornsby was arguably one of the five or ten greatest baseball players, ever. He has the second-highest career batting average, ever. He had six seasons where he posted at least 10 Wins Above Replacement, equaling Barry Bonds and one fewer than Willie Mays. (On the high-end, Babe Ruth had ten; Hank Aaron, though, had none.)

In 1922, Hornsby won the first of his Triple Crowns, meaning that he led the National League - all 8 teams - in batting average (AVG), home runs (HR), and runs batted in (RBI). In 1925, he did it again, but did it even better. This time, he led all of Major League Baseball in average, homers, and batted in.

4.

This season, Miguel Cabrera led the American League in that baseball traditionalist's favorite fetishistic triumvirate of stats: AVG, HR, RBI. (It's actually eminently reasonable to fetishize HR, because there's no better indicator of raw power. But AVG is demonstrably inferior to on-base percentage at demonstrating what it's supposed to demonstrate, and RBI is almost useless - it's an opportunity stat, and not particularly reflective of ability. Plenty of awful players have driven in 100 RBI, provided that they hit in the middle of the order and get to play every game.)

But the American League, like the Eastern Conference, is just a subset of half the teams in the whole of Major League Baseball. Cabrera led all of baseball in HR and RBI, but came second (or third, arguably) league-wide in AVG, behind the National League's Buster Posey. Actually, he didn't even lead all Cabreras in AVG - the NL's Melky Cabrera was more than ten points higher, though he was one plate appearance short of "qualifying" for the batting title. (Although, that said, baseball has a rule that allows him to qualify by adding an extra "out" to his season line. Melky Cabrera requested that they not that, and they complied, but we don't have to also indulge him.)

5.

Last season, Matt Kemp hit .324 with 39 HR and 126 RBI - a season very similar to the one that Miguel Cabrera just put up this year. But Kemp didn't win the Triple Crown and didn't win the MVP. (Although he probably should have. Even if we concede that he and MVP Ryan Braun were nearly identical as hitters, Kemp is a substantially better fielder at a much harder position.) Kemp led the National league is HR and RBI, and finished third in AVG. He also led all of baseball in RBI, was 3rd in HR, and 7th in AVG.

But let's be playful, for a moment, and try to imagine how Kemp could have won the Triple Crown.

Among National Leaguers, players on only the Brewers and Mets beat Kemp's batting average. Among American Leaguers, players on only the Yankees, Red Sox, Rangers, Tigers, and Blue Jays beat Kemp's AVG or HR. That means that Kemp's Triple Crown numbers were better than those posted by any player on the other 23 teams. Substitute the Brewers and Mets with any of the other 9 American League teams, and suddenly Matt Kemp has won a Triple Crown.

Actually, it's even easier than that. There are 14 teams in the AL and 16 in the NL. Miguel Cabrera had the best Triple Crown numbers among the players from 14 teams. Matt Kemp also had the best numbers among a group of 14 teams, but had the misfortune of playing in the larger League. If you drop the Brewers and Mets, you're left with 14 teams - the exact same number of teams and players that Cabrera was in competition with.

5.

Getting to the point: The MVPs of baseball's two Leagues will be announced on Thursday, and the American League's MVP Trout vs. Cabrera race is being figured as something much bigger than the two players themselves: advanced stats vs. traditional ones, Wins Above Replacement (WAR) vs. the Triple Crown. But I'm going to suggest that this framing of the competition begs the question: because before we can ask whether it's more important to lead the league in WAR or in Triple Crown stats, we should probably confirm that Miguel Cabrera actually won the Triple Crown.

Baseball fans are probably perplexed, at this point - because Cabrera did win the Triple Crown, didn't he? Major League Baseball even created a trophy for it:

Obnoxious trophies aside, I'm gonna say it: Cabrera won squat. If Stamkos wasn't the Eastern Conference's Richard Trophy winner, if Kemp didn't also win a Triple Crown, then it makes zero sense for Cabrera to be the American League's Triple Crown winner. It's based on an arbitrary assignment of 14 teams to one League and 16 to another. It's misleading, at least insofar as people routinely refer to the Triple Crown as "baseball's Triple Crown". It's not a real Triple Crown.

Rogers Hornsby in 1925, leading all of baseball in the Triple Crown stats? That's a real Triple Crown, just like Corey Perry's 50 goals earned him a real Maurice Richard Trophy. Cabrera's impressive but nonetheless second-(or third-)best batting average? Second-best won Stamkos zero Richard trophies, which is precisely the number of Triple Crowns (and MVP awards) that Cabrera deserves.

6.

Additionally hilarious thought: I'm willing to bet that the same people who would give Cabrera the MVP over Trout because the former won the AL Triple Crown would see things differently if there was only one MVP and not one for each league - you know, just like every other pro sports league. Because then we definitely wouldn't be talking about this Triple Crown thing - and without that traditionalist fetish symbol obscuring the view, Trout's superior numbers and performance are a whole lot easier to see.

Here's the thing, and the whole point of how hilariously inappropriate and deceptive the Triple Crown award actually is: if a player is the MVP of his league, then he should be the MVP regardless of (ostensibly) irrelevant alternatives. If Cabrera > Trout, then that should hold true whether we're considering him for AL MVP or the MVP of all baseball. But that's not actually true. Because Cabrera's argument hinges so totally on his Triple Crown. If we consider all of baseball - AL and NL - including Buster Posey (or Melky Cabrera) and his higher batting average, then Cabrera loses the Triple Crown and suddenly Trout > Cabrera. That's absurd. And, yet, that's how baseball traditionalists think.

In the NHL's 2010-2011 season, Daniel Sedin - a player in the Western Conference - led the league with 104 points and won the Art Ross Trophy as the leading scorer. The Eastern Conference's Martin St. Louis scored 99 points, second-best in the NHL, and was awarded nothing. Corey Perry - another Western Conference player - led the league with 50 goals and was awarded the Maurice Richard Trophy as top goal-scorer. Martin St. Louis's teammate, Steven Stamkos, scored 45 to lead the Eastern Conference, but nobody noticed or cared.

2.

One of the oft-repeated arguments in favor of pitcher Jack Morris's election to the baseball Hall of Fame is that he led baseball in Pitcher Wins during the 1980s, with 162, and every other pitcher who led a particular decade in Pitcher Wins is in the Hall of Fame. Let's ignore, for the moment, that this is actually a pretty meaningless stat - that Pitcher Wins are heavily dependent on the quality of the pitcher's team, as well as dependent on having a lot of opportunities to start, and that we have much better stats available - and see whether that's actually true.

From 1977-1986 - a full decade - Ron Guidry led baseball with 163 Pitcher Wins. (Morris had 144 over the same time-frame.) Ron Guidry is not in the Hall of Fame. From 1984-1993, Frank Viola and Roger Clemens tied for the most Pitcher Wins, again with 1963. Frank Viola is also not in the Hall of Fame, and Clemens will be hard-pressed to shake the steroid-user label and qualify for the Hall, at least for the first few years.

So, even if I limit myself to the years where Morris was also active, it's pretty clear that the argument falls apart unless it's hilariously constrained. It's all about the easy and ready-made reference points, apparently.

3.

Rogers Hornsby was arguably one of the five or ten greatest baseball players, ever. He has the second-highest career batting average, ever. He had six seasons where he posted at least 10 Wins Above Replacement, equaling Barry Bonds and one fewer than Willie Mays. (On the high-end, Babe Ruth had ten; Hank Aaron, though, had none.)

In 1922, Hornsby won the first of his Triple Crowns, meaning that he led the National League - all 8 teams - in batting average (AVG), home runs (HR), and runs batted in (RBI). In 1925, he did it again, but did it even better. This time, he led all of Major League Baseball in average, homers, and batted in.

4.

This season, Miguel Cabrera led the American League in that baseball traditionalist's favorite fetishistic triumvirate of stats: AVG, HR, RBI. (It's actually eminently reasonable to fetishize HR, because there's no better indicator of raw power. But AVG is demonstrably inferior to on-base percentage at demonstrating what it's supposed to demonstrate, and RBI is almost useless - it's an opportunity stat, and not particularly reflective of ability. Plenty of awful players have driven in 100 RBI, provided that they hit in the middle of the order and get to play every game.)

But the American League, like the Eastern Conference, is just a subset of half the teams in the whole of Major League Baseball. Cabrera led all of baseball in HR and RBI, but came second (or third, arguably) league-wide in AVG, behind the National League's Buster Posey. Actually, he didn't even lead all Cabreras in AVG - the NL's Melky Cabrera was more than ten points higher, though he was one plate appearance short of "qualifying" for the batting title. (Although, that said, baseball has a rule that allows him to qualify by adding an extra "out" to his season line. Melky Cabrera requested that they not that, and they complied, but we don't have to also indulge him.)

5.

Last season, Matt Kemp hit .324 with 39 HR and 126 RBI - a season very similar to the one that Miguel Cabrera just put up this year. But Kemp didn't win the Triple Crown and didn't win the MVP. (Although he probably should have. Even if we concede that he and MVP Ryan Braun were nearly identical as hitters, Kemp is a substantially better fielder at a much harder position.) Kemp led the National league is HR and RBI, and finished third in AVG. He also led all of baseball in RBI, was 3rd in HR, and 7th in AVG.

But let's be playful, for a moment, and try to imagine how Kemp could have won the Triple Crown.

Among National Leaguers, players on only the Brewers and Mets beat Kemp's batting average. Among American Leaguers, players on only the Yankees, Red Sox, Rangers, Tigers, and Blue Jays beat Kemp's AVG or HR. That means that Kemp's Triple Crown numbers were better than those posted by any player on the other 23 teams. Substitute the Brewers and Mets with any of the other 9 American League teams, and suddenly Matt Kemp has won a Triple Crown.

Actually, it's even easier than that. There are 14 teams in the AL and 16 in the NL. Miguel Cabrera had the best Triple Crown numbers among the players from 14 teams. Matt Kemp also had the best numbers among a group of 14 teams, but had the misfortune of playing in the larger League. If you drop the Brewers and Mets, you're left with 14 teams - the exact same number of teams and players that Cabrera was in competition with.

5.

Getting to the point: The MVPs of baseball's two Leagues will be announced on Thursday, and the American League's MVP Trout vs. Cabrera race is being figured as something much bigger than the two players themselves: advanced stats vs. traditional ones, Wins Above Replacement (WAR) vs. the Triple Crown. But I'm going to suggest that this framing of the competition begs the question: because before we can ask whether it's more important to lead the league in WAR or in Triple Crown stats, we should probably confirm that Miguel Cabrera actually won the Triple Crown.

Baseball fans are probably perplexed, at this point - because Cabrera did win the Triple Crown, didn't he? Major League Baseball even created a trophy for it:

Obnoxious trophies aside, I'm gonna say it: Cabrera won squat. If Stamkos wasn't the Eastern Conference's Richard Trophy winner, if Kemp didn't also win a Triple Crown, then it makes zero sense for Cabrera to be the American League's Triple Crown winner. It's based on an arbitrary assignment of 14 teams to one League and 16 to another. It's misleading, at least insofar as people routinely refer to the Triple Crown as "baseball's Triple Crown". It's not a real Triple Crown.

Rogers Hornsby in 1925, leading all of baseball in the Triple Crown stats? That's a real Triple Crown, just like Corey Perry's 50 goals earned him a real Maurice Richard Trophy. Cabrera's impressive but nonetheless second-(or third-)best batting average? Second-best won Stamkos zero Richard trophies, which is precisely the number of Triple Crowns (and MVP awards) that Cabrera deserves.

6.

Additionally hilarious thought: I'm willing to bet that the same people who would give Cabrera the MVP over Trout because the former won the AL Triple Crown would see things differently if there was only one MVP and not one for each league - you know, just like every other pro sports league. Because then we definitely wouldn't be talking about this Triple Crown thing - and without that traditionalist fetish symbol obscuring the view, Trout's superior numbers and performance are a whole lot easier to see.

Here's the thing, and the whole point of how hilariously inappropriate and deceptive the Triple Crown award actually is: if a player is the MVP of his league, then he should be the MVP regardless of (ostensibly) irrelevant alternatives. If Cabrera > Trout, then that should hold true whether we're considering him for AL MVP or the MVP of all baseball. But that's not actually true. Because Cabrera's argument hinges so totally on his Triple Crown. If we consider all of baseball - AL and NL - including Buster Posey (or Melky Cabrera) and his higher batting average, then Cabrera loses the Triple Crown and suddenly Trout > Cabrera. That's absurd. And, yet, that's how baseball traditionalists think.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

A knock on the defense offered for Yunel Escobar

A brief update on the ongoing Yunel Escobar and the "tu ere maricon" controversy, which I first blogged about here and here.

The common defense that's being used, in the hours and days following the press conference, is that the possible negative connotation of the word is being overblown. Latin American players and reporters have been quick to say that there's a translation problem - both linguistically and culturally speaking - and that it really wasn't a big deal. "Maricon" means a lot of things, they say, and lots of people use it everyday and in casual conversation with friends and family. So, no problem, right?

Well, I don't really buy it. In fact, the culture-gap/culture-clash defense strikes me as pretty weak. Worse, it strikes me as, at best, a bit clueless and, at worst, indicative of a much larger problem with homophobia and a misunderstanding of how it operates and perpetuates. (And I'm not even gonna go anywhere near the "boys will be boys" type of defense that's been offered by Dirk Hayhurst and others. Honestly, if I need to explain why that one is unbelievably fucking problematic, you're probably not going to understand anything that follows, anyway.)

Players and coaches like Omar Vizquel and Ozzie Guillen quickly defended Escobar by saying that Latin Americans use the word in casual conversation with their friends all the time, to show them affection, to tease them, and/or to emasculate them.

Now, admittedly, I'm no expert or cultural anthopologist with expertise with respect to the Caribbean. But I am keenly aware of just how much more dangerous it is to be an LGBTQ person in Central America than it is in Canada. And that difference, that danger? I'm going to suggest that it has a lot to do with the ease with which people like Vizquel and Guillen can brush aside Escobar's words. (Just a quick note: I am not so naive as to think that race isn't playing a factor in the way that the Toronto media has taken up the story. But that's another story for another day.)

Because this defense sounds an awful lot like "when we say 'fag', we mean you're too sensitive. we don't mean you're gay or anything'." This sounds an awful lot like "when i say he's a 'pussy', i mean he's weak. it doesn't have anything to do with women, so it can't be sexist". It sounds like they don't recognize the implied equivalence - that if, say, "pussy" means "weak" but it also means "woman", then a connection is implied between "weak" and "woman". It sounds like they're pretending - or are genuinely oblivious to - the power that words carry, the things that they say in excess of what we intend for them to say all the time.

And that power? It doesn't go away if we stop acknowledging it - it just becomes invisible. As Irene Monroe puts it, in her coverage of this story, "if the phrase 'TU ERE MARICON' goes unchecked or is not challenged, it allows people within their culture to become unconscious and numb to the use and abuse of the power and currency of this homophobic epithet -- and the power it still has to thwart the daily struggles of many of us to ameliorate LGBTQ relations." Being unconscious or numb to the word's connotations through overuse isn't a good excuse - like I said before, it's indicative of the larger, systemic problem.

The response of people like Guillen and Vizquel is also a remarkably unempathetic. Every one of these responses has, from what I can tell, been offered by straight Latin American men who use it in conversation with other straight Latin American men and note that other straight Latin American men don't find it all shocking. WHAT A SURPRISE. But what about all of the gay men that they talk to? (I mean, in addition to the men that Escobar employs.) Or that don't talk to them because the language makes them feel unsafe? Or, worse yet, who join in the discourse because they would feel more unsafe if they didn't play along? Because - guess what? - that happens all the time. They don't exist, I guess. In fact, if the media-response outside a couple papers in Toronto is any indication, the whole queer community doesn't exist! Or, you know, you could look for them, because you would find them.

As a totally unrelated aside, I can recall the comic book creator John Byrne explaining that, when he was a kid growing up in England during the 50s, it was not uncommon for the English to use the word "nigger" in everyday conversation. He said that it was even relatively common, at least where he grew up, to give the name "Nigger" to cats and dogs. And, he adds, it wasn't racist at all! But how's that possible, you ask? Because the white people who used it didn't think it was racist.

That makes sense, right? A bunch of white people casually use a derogatory word for non-white people, and they apply it endearingly to animals and, of course, without malice or intent to harm - so that's totally cool, right? Because who could be offended by a word loaded with painful historical baggage? Who could be offended if that word's given as a name to a dog? End of story.

And if that logic strikes you as totally fucked up... then maybe you can see that I was lying when I said it was a totally unrelated aside.

The common defense that's being used, in the hours and days following the press conference, is that the possible negative connotation of the word is being overblown. Latin American players and reporters have been quick to say that there's a translation problem - both linguistically and culturally speaking - and that it really wasn't a big deal. "Maricon" means a lot of things, they say, and lots of people use it everyday and in casual conversation with friends and family. So, no problem, right?

Well, I don't really buy it. In fact, the culture-gap/culture-clash defense strikes me as pretty weak. Worse, it strikes me as, at best, a bit clueless and, at worst, indicative of a much larger problem with homophobia and a misunderstanding of how it operates and perpetuates. (And I'm not even gonna go anywhere near the "boys will be boys" type of defense that's been offered by Dirk Hayhurst and others. Honestly, if I need to explain why that one is unbelievably fucking problematic, you're probably not going to understand anything that follows, anyway.)

Players and coaches like Omar Vizquel and Ozzie Guillen quickly defended Escobar by saying that Latin Americans use the word in casual conversation with their friends all the time, to show them affection, to tease them, and/or to emasculate them.

- Vizquel: "We say that word very often, and to us, it doesn’t really mean that we are decreasing anybody or talking down to people or anything like that. It’s just a word we use on an everyday basis. I don’t know why people are taking this so hard and so out of place or out of proportion."

- Guillen: "In my house, we call (each other) that word every 20 seconds. I've got three kids," Guillen added. "For us, it's like 'What's up, bro? What's up, dude?' It's how you say it and to who you say it. But that's our country.

Now, admittedly, I'm no expert or cultural anthopologist with expertise with respect to the Caribbean. But I am keenly aware of just how much more dangerous it is to be an LGBTQ person in Central America than it is in Canada. And that difference, that danger? I'm going to suggest that it has a lot to do with the ease with which people like Vizquel and Guillen can brush aside Escobar's words. (Just a quick note: I am not so naive as to think that race isn't playing a factor in the way that the Toronto media has taken up the story. But that's another story for another day.)

Because this defense sounds an awful lot like "when we say 'fag', we mean you're too sensitive. we don't mean you're gay or anything'." This sounds an awful lot like "when i say he's a 'pussy', i mean he's weak. it doesn't have anything to do with women, so it can't be sexist". It sounds like they don't recognize the implied equivalence - that if, say, "pussy" means "weak" but it also means "woman", then a connection is implied between "weak" and "woman". It sounds like they're pretending - or are genuinely oblivious to - the power that words carry, the things that they say in excess of what we intend for them to say all the time.

And that power? It doesn't go away if we stop acknowledging it - it just becomes invisible. As Irene Monroe puts it, in her coverage of this story, "if the phrase 'TU ERE MARICON' goes unchecked or is not challenged, it allows people within their culture to become unconscious and numb to the use and abuse of the power and currency of this homophobic epithet -- and the power it still has to thwart the daily struggles of many of us to ameliorate LGBTQ relations." Being unconscious or numb to the word's connotations through overuse isn't a good excuse - like I said before, it's indicative of the larger, systemic problem.

The response of people like Guillen and Vizquel is also a remarkably unempathetic. Every one of these responses has, from what I can tell, been offered by straight Latin American men who use it in conversation with other straight Latin American men and note that other straight Latin American men don't find it all shocking. WHAT A SURPRISE. But what about all of the gay men that they talk to? (I mean, in addition to the men that Escobar employs.) Or that don't talk to them because the language makes them feel unsafe? Or, worse yet, who join in the discourse because they would feel more unsafe if they didn't play along? Because - guess what? - that happens all the time. They don't exist, I guess. In fact, if the media-response outside a couple papers in Toronto is any indication, the whole queer community doesn't exist! Or, you know, you could look for them, because you would find them.

* * *

As a totally unrelated aside, I can recall the comic book creator John Byrne explaining that, when he was a kid growing up in England during the 50s, it was not uncommon for the English to use the word "nigger" in everyday conversation. He said that it was even relatively common, at least where he grew up, to give the name "Nigger" to cats and dogs. And, he adds, it wasn't racist at all! But how's that possible, you ask? Because the white people who used it didn't think it was racist.

That makes sense, right? A bunch of white people casually use a derogatory word for non-white people, and they apply it endearingly to animals and, of course, without malice or intent to harm - so that's totally cool, right? Because who could be offended by a word loaded with painful historical baggage? Who could be offended if that word's given as a name to a dog? End of story.

And if that logic strikes you as totally fucked up... then maybe you can see that I was lying when I said it was a totally unrelated aside.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

The Yunel Escobar press conference: well, that was a complete disaster

If I'm being charitable, there are two things that went right with the 30-minute press conference that ended less than a half-hour ago, where Yunel Escobar and the Blue Jays were asked to explain why he wrote, in Spanish, "you're a faggot/pussy" under his eyes. (You can find the picture in a blog I wrote yesterday, found here.)

And that's it. And that covers two or three minutes of the content of the press conference. So, what went wrong? All of it, pretty much:

- He apologized and said it won't happen again.

- The Blue Jays will donate money to You Can Play, a Toronto-based charity that combats homophobia in sports.

And that's it. And that covers two or three minutes of the content of the press conference. So, what went wrong? All of it, pretty much:

- Escobar said the words "didn't mean anything", that he didn't "intend to offend anyone", and it was "misinterpreted". As far as apologies go, this veers dangerously close to victim-blaming. That is, he implied nothing, which means it's our fault for inferring something hurtful. And that's bullshit.

- Escobar - and his teammate Edwin Encarnacion, via reporter Shi Davidi - said that the slur isn't necessarily a slur, depending on the "context" (Escobar's word, via a translator). Encarnacion said it was a "joke". Right. Just like when someone, for instance, uses "gay" but actually means 'ugly' or 'stupid'? That's a joke too. In no way are they implying an equivalence between "gay" and "stupid". No, not at all. It's just a joke.

- And what of "context", anyway? Escobar said it wasn't meant to be read by anyone. (Which is curious, since the manager, John Farrell, said that he often writes words under his eyes, and they're usually inspirational. Which suggests that they can and are meant to be read. But that's not the most egregious failure of communication between staff and players. More on that in a bit...) I don't know whether he's being disingenuous or he's actually that stupid, but there's no explanation that makes sense except to assume that he was directing it at the Boston Red Sox - the team the Jays were playing that day. And if he's directing it at the opposition? Well, that context lends itself to the interpretation that he did mean to call them "fags" or "pussies", and that he did mean it pejoratively. No other conclusion makes sense.

- That other moment where Farrell wasn't quite credible? It took forever, but one of the reporters eventually asked whether homophobia is a problem in baseball locker rooms. (A classic response to this kind of incident is to frame it as an isolated incident - to invoke the "one rotten apple" fallacy.) And Farrell completely blew it. He said it isn't a problem, but any of us who have played sports at any level know that he's hilariously wrong. As Dirk Hayhurst, the former Blue Jay, wrote yesterday, "Crude, offensive humor is a part of the lexicon of the clubhouse. Always has been, probably always will be." So, let's be honest, at least. Because telling such a transparent lie just totally destroys your believability.

- And Farrell dropped the ball at least one more time, too. When asked why he didn't notice the words, he said that doesn't pay attention to them, and that no one really does. And he didn't admit that he should be looking - in fact, he took no responsibility at all. That's a catastrophic failure of leadership. The first words out of Farrell's mouth should have been an admission of fault - an admission that he didn't look, but he should have. While, sure, Escobar deserves blame for hilariously poor judgement, Farrell is the guy letting him write on his face and failing to vet those same words. And, plain and simple, he's the boss. A huge part of the manager's job in baseball is to take pressure off of his players, to mediate between players and umpires, players and management, players and media, players and players... But Farrell just threw Escobar to the wolves.

- This next criticism applies to everyone who was sitting on the panel. Until a reporter said the word "homophobia", not one of them used the word. Escobar and his translator said "gay", (as in, embarrassingly, "my hairdresser is gay") but no one addressed the elephant in the room directly. What they did do was admit that there was a "problem". Repeatedly, Farrell and the GM, Alex Anthopolous, referred to homophobia as "the problem". A problem so serious, evidently, that we can't even refer to it by name. For fuck's sake, guys. Couldn't you have spoken to a subject matter expert or PR consultant before doing this? Couldn't you at least bring a diversity or sensitivity trainer in to coach you? Which leads me to my final point...

- ...which is that, aside from throwing $90k or so to charity, it felt like the Jays came into this press conference with no plan at all. No talking-points that made sense, no idea of how to talk about the issue, no clear indication that they had received advice or vocabulary (much less some quick mediation or counselling) from a gay rights or equity or anti-oppressive educator. (Hey, Blue Jays! I can even recommend my friend to you!) They. Looked. Totally. Lost. And what might the Jays or Escobar do after the money is donated? I have absolutely no idea. Hope that everyone forgets, maybe? Yeah, that sounds about right.

Thursday, August 09, 2012

Olympic soccer: rules and dives

Two quick responses to Olympic women's soccer:

1) Without getting into too much detail - because if you care, you already know; and if you don't, you can just read about it here - a semi-final game in Olympic soccer might have been decided by a referee's decision to invoke an arcane and rarely used rule that says a goalkeeper can't hold on to the ball for more than 6 seconds. (How rare and arcane? Apparently, no sports writer can find mention of it in an international or major domestic league game - men's or women's - since 2002. That's ten years, and probably tens of thousands of games.) What makes this rule especially damaging is that the opposing team is awarded a free-kick directly in front of the goal.

For baseball fans, this would be like enforcing the "12-second" rule for pitchers. What "12-second" rule, you ask? The one that's never actually used, yet remains in the rulebook:

Hilariously, the average pitcher in Major League Baseball is nowhere near the ostensible "limit" of 12 seconds per possession - it's actually more like 20. And yet, an umpire could suddenly decide to call this rule, and the pitcher would have no substantive reason to object, except on the grounds that no one calls it. Which is simply a disaster waiting to happen. If officials don't use it, the rulebook should lose it.

2) I often find men's soccer painful to watch. It's the diving. I just can't stand to watch people pretend to be fouled and then pretend to be hurt. And I like watching women's soccer because it there's almost none of that. And not only is there virtually no diving, but it seems like these women will collide and run over each other and get right back up - to put it simply, they 'suck it up'.

At first, this seems really unintuitive. We expect women's sports to have (patronizing) rules in place to protect them - women's hockey, for instance, doesn't allow body checking at any level - and we expect, in North America, at least, that men will behave in typically masculine ways and eschew diving or any other behavior that might make them seem weak.

That last bit might be the important part, though. When I was watching Canada play Great Britain, the commentators suggested that the stylistic difference between the women's and men's games was cultural - the women's game, and it's first powerhouse-teams - emerged in the USA and East Asia, where diving in any sport has never been valued, and those values were emulated by other countries. Now, I don't know that this is an adequate explanation. Most of the women's teams are coached and trained by European men, after all. But it's certainly interesting. (And certainly problematic, since it's that masculine ethic of playing through the pain and self-destructive behavior that I've criticized again and again. And which, clearly, I value in spite of that.)

1) Without getting into too much detail - because if you care, you already know; and if you don't, you can just read about it here - a semi-final game in Olympic soccer might have been decided by a referee's decision to invoke an arcane and rarely used rule that says a goalkeeper can't hold on to the ball for more than 6 seconds. (How rare and arcane? Apparently, no sports writer can find mention of it in an international or major domestic league game - men's or women's - since 2002. That's ten years, and probably tens of thousands of games.) What makes this rule especially damaging is that the opposing team is awarded a free-kick directly in front of the goal.

For baseball fans, this would be like enforcing the "12-second" rule for pitchers. What "12-second" rule, you ask? The one that's never actually used, yet remains in the rulebook:

8.04 When the bases are unoccupied, the pitcher shall deliver the ball to the batter within 12 seconds after he receives the ball. Each time the pitcher delays the game by violating this rule, the umpire shall call “Ball.” The 12-second timing starts when the pitcher is in possession of the ball and the batter is in the box, alert to the pitcher. The timing stops when the pitcher releases the ball.

Hilariously, the average pitcher in Major League Baseball is nowhere near the ostensible "limit" of 12 seconds per possession - it's actually more like 20. And yet, an umpire could suddenly decide to call this rule, and the pitcher would have no substantive reason to object, except on the grounds that no one calls it. Which is simply a disaster waiting to happen. If officials don't use it, the rulebook should lose it.

* * *

2) I often find men's soccer painful to watch. It's the diving. I just can't stand to watch people pretend to be fouled and then pretend to be hurt. And I like watching women's soccer because it there's almost none of that. And not only is there virtually no diving, but it seems like these women will collide and run over each other and get right back up - to put it simply, they 'suck it up'.

At first, this seems really unintuitive. We expect women's sports to have (patronizing) rules in place to protect them - women's hockey, for instance, doesn't allow body checking at any level - and we expect, in North America, at least, that men will behave in typically masculine ways and eschew diving or any other behavior that might make them seem weak.

That last bit might be the important part, though. When I was watching Canada play Great Britain, the commentators suggested that the stylistic difference between the women's and men's games was cultural - the women's game, and it's first powerhouse-teams - emerged in the USA and East Asia, where diving in any sport has never been valued, and those values were emulated by other countries. Now, I don't know that this is an adequate explanation. Most of the women's teams are coached and trained by European men, after all. But it's certainly interesting. (And certainly problematic, since it's that masculine ethic of playing through the pain and self-destructive behavior that I've criticized again and again. And which, clearly, I value in spite of that.)

Saturday, July 28, 2012

Mocking the London Olympics' Opening Ceremonies

The Opening Ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics made all sorts of references to the children's literature that's been produced by British authors: Mary Poppins, Peter Pan, and Harry Potter were all rather prominent. But the book - or series of books, rather - that seemed to dominate the show was never actually referred to by name.